For the past year, I’ve been researching the manifestation and vernacular of Marian apparitions. I’ve been dreaming of Teresita Castillo, Angel dela Vega, Nora Aunor, and the women in my life; connecting technology & femininity and what becomes of us.

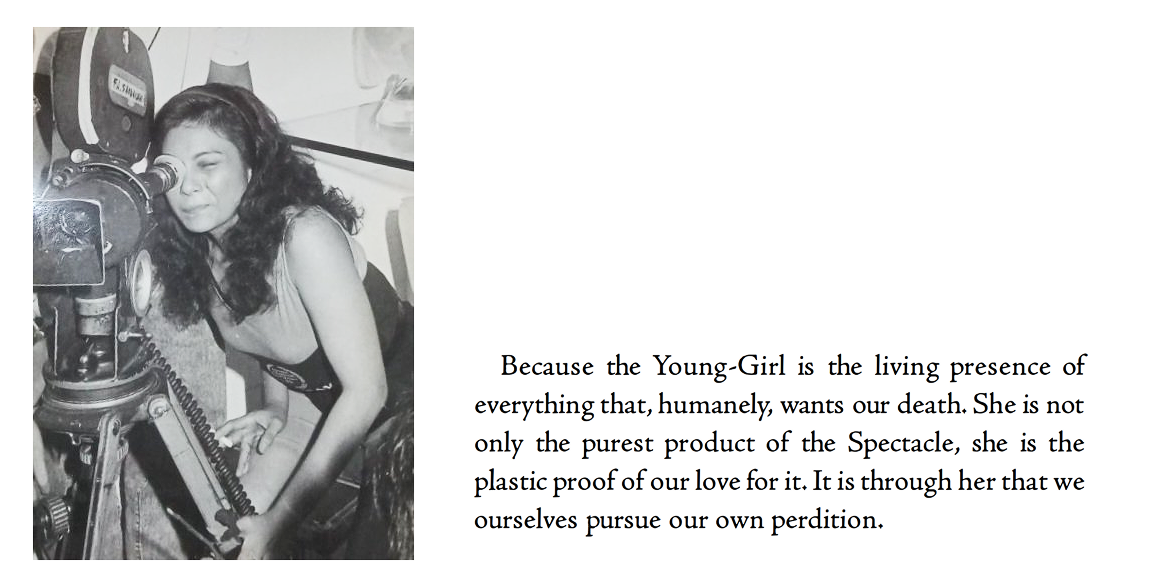

Ishmael Bernal’s Himala (1982) has been central in my unpacking of Mariology and apparition in today’s technological world. The film follows the descent of a feminine visionary Elsa, and the documentation of her belief, assault, renunciation and hereticism. Since Nora Aunor, who plays Elsa’s passing, I wanted to revisit the film more in the context of the (already much theorized) implications of her stardom’s influence on the film’s conceit around vision/image and hysteria/idolatry. As I’ll go on to describe, it is impossible to read any text on Himala without the shadow of Aunor; while I haven’t seen her work outside of it, knowing the film made her loss leave an impression on me… her mythology mirrors so much of the Filipino’s relation with Mary, and I can sense all the lives within her.

This is a scattering of thoughts about idolatry, cyberfeminism, suffering, and faith. It is a tiny tribute after Nora Aunor’s passing, and a reflection of “the girl” & its related theory with the “Noranian Imaginary”—an attempt to toss in the Filipino eye to our unfoldings of Catholic technologies.

(There are often many years in my life where I forget to pray, but I always start to remember…)

THE END OF THE WORLD

You are here my child, in this little humble mountain that my Son chose, like yourself, the little humble instrument of God, who will bring my children to come to the Mountain of salvation of Peace, Love, and Joy…

Message of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception at the Mountain of Salvation, Batangas, Philippines

You, my children, are here because God called you to be his instruments, to spread the message of love…

Nora Aunor’s stardom cannot be divorced from all she is. Her rags-to-riches life, humility, and faith lay the groundwork for every character she plays, turning every screen into a shimmering mirror, reflecting the watcher back at her. This is not just acting—the girl extends her life and its legend through every scene. In Himala, this is all at its truest: Aunor stars not only as Elsa, but herself in a spectacle of belief and screen. When she passed this April 2025, some declared that cinema itself had ended.

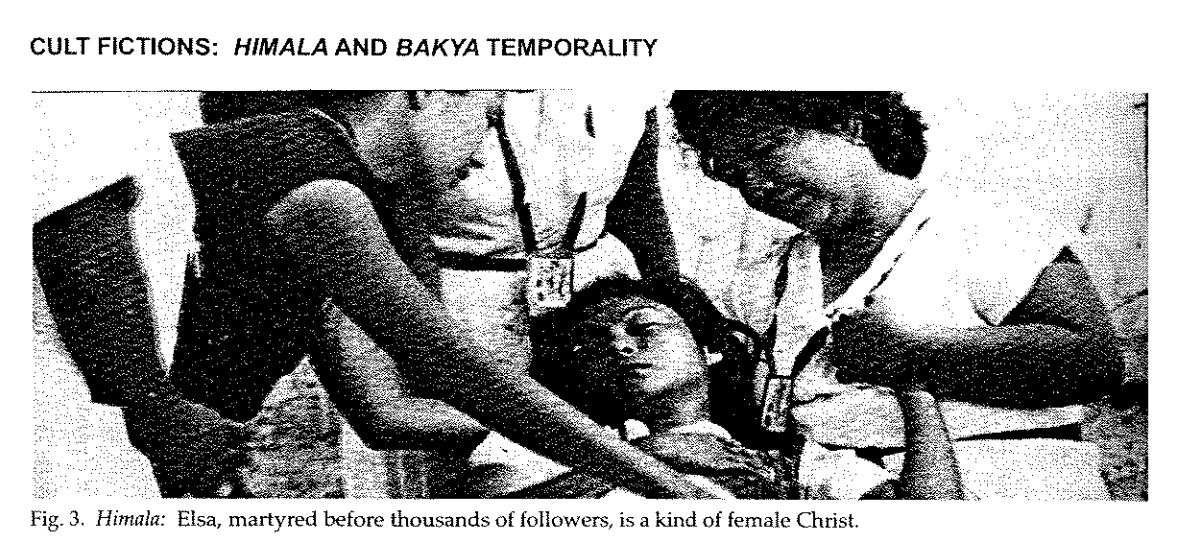

Himala begins at the end of the world. Under blackened sky on barren hill, Elsa (Nora Aunor) sees an apparition of the Virgin Mary. We hear the calling with her, her ecstatic, blissful stare into the dark — a hint of something beyond — bliss after nothingness, agony after bliss. Torment in the chest. Then, her eyes are lifeless, tears fall, crying as the wounded Mary fades. Heretical, a demon inside her. One more day into the hill. Her hands are bloodied with stigmata. She begins engaging in faith healing despite disbelief from the men around her, and her once-poverty-stricken town finds renewed life in the pilgrims seeking Elsa’s prayer and miracle-making; a godless filmmaker even begins documenting her life, funded from his own pocket (the film is in itself, documentary-like in its eye & cinematography), and a brothel is opened for tourists. One afternoon, the filmmaker documents some boys raping Elsa and her main attendant—capturing a brutal truth and letting the camera play god. Soon, an epidemic spreads that faith alone cannot resolve, Elsa’s attendant commits suicide out of shame, and Elsa slowly deals with the people’s loss of resolve and a pregnany resulting from the assault—this virgin birth is enough to reignite people’s belief in her. At the film’s climax, she lets out an impassioned speech declaring that there are no miracles, “walang himala!”, and that all gods, good, and darkness are the invention of man. She is shot after this declaration, with her followers scattering and suffering in a stampede. In her last moments, her arms are outstretched, assuming the position of God, crucified.

Let us honour Mary, for such is the will of God, Who would have us obtain everything through the hands of Mary.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermon for the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary

For Elsa, the end is the beginning of belief.

In her derelict town, the only sign of faith becomes her healing (her faith), which begins to spiral out of proportion as she continues to oblige and amass attendants for. She senses this spiritual deprivation, feeds upon it. Network effects: a sea of arms clawing to touch her, wanting her, needing her for salvation. Kissing her, grabbing her, clutching her as she wades through; they are all hungry, poverty-stricken, the most abandoned of the world. “We are poor. There’s nothing left for us but faith.” Her sight in Mary starts to be further affirmed as others see through her, with these healing acts becoming stand-ins for the missing material evidence for her conviction in Mary (otherwise, is she a victim to her own delusion from the very beginning?)—the body becomes a channel for belief. Elsa clarifies: her hands aren’t doing the healing, it’s Mary’s. All that she conduits is whatever God seeks to provide, attempting to answer what people seek. In the fall, the reward for devotion is always delusion.

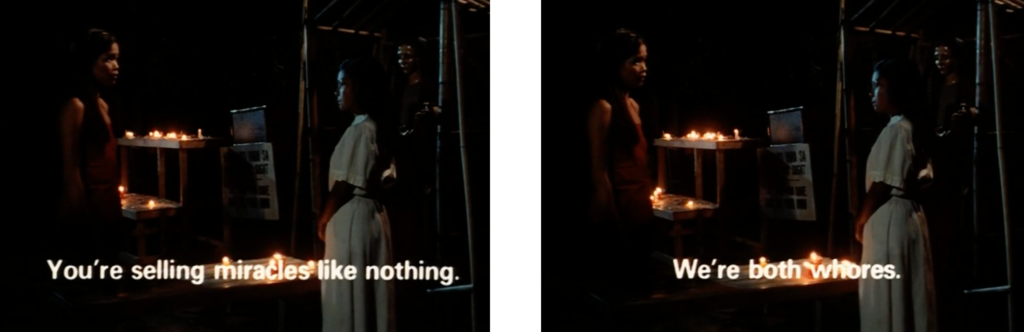

Women are placed in this precarious position where our desires are taken from us and redefined, subjugating us as we embody and realize these distortions to their completion. The town’s desolation is filled by Elsa’s preachings and the rains come again to its arid place after Elsa is found pregnant against her will. Imitating Mary once more, the people rejoice at this likeliness, not knowing of the truth of her carrying. Every violation makes her more holy, only this warping of her body and soul furthers her as a channel — she is less like a human, but more like a network. The lead of the brothel confronts Elsa: “Pinagbilhan niyo sila ng mga himala. Pareho lang tayong puta.” You sold miracles. We’re both just whores.

Everything is projected unto the girl: personal sickness, violent sexual desire, responsibility for the skies above; the miracle comes from her continuous taking, repression, and delusion. People are poor in more ways than hand and mind, and only in this entire taking of Elsa can they be sickly satisfied. As our desire is transmuted, we are almost manipulated into clinging to beliefs no longer ours—perhaps out of a desperation to reject this loss of control, or an actual compromising of our own belief as the world around us shifts ceaselessly. Women carry the consequence of not just their own belief, but every delusion imposed unto them. She has no choice but to feed into a hysteria; the end and the beginning is a tragedy of belief. Watching droves of people arrive in Cupang felt almost like an understatement to the swarms in Filipino religious festivities; devotees get violent when they try to kiss the feet of statues and figures, and girls go insane as all they see is relegated to the peripheries. It places all the theatrics of the small “Elsa Loves You” parade in the shame—hardly an exaggeration, just a repetition of our desolation. All Elsa does is feed into the hunger, serve as a way for people to get closer to god, soon become god itself. The film marks Aunor’s canonization; she is now a superstar, one of the closest roles to modern ‘faith healing’ the nation carries—healing, prophesizing, shocking, and dying on screen for us over and over again. Elsa/Nora are tools, objects, machines, messiahs; in their degradation are they the most sanctified.

For as a man in his intellective powers participates in the Divine knowledge through the virtue of faith, and in his power of will participates in the Divine love through the virtue of charity, so also in the nature of the soul does he participate in the Divine Nature, after the manner of a likeness, through a certain regeneration or re-creation.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica

A LOOKING

Interspersed throughout this text are quotations from Tiqqun’s Young-Girl, a dissection and theory towards the Young-Girl (or reduced here to “girl”) as capitalism’s model; a frame that Elsa / Nora simultaneously embodies, refutes, and transgresses. The figure of one who has her desires assigned to her by the market, yet appears to choose, or even demands these desires. Surfacely, Elsa turns her body into that of a commodity, given value and authority from both the domestic and divine, sculpting the soil and soul all around her. Nora plays a fiction that is still so clearly a familiar real. The camera records a camera, we watch a star grow into another star.

Just as the women in Elsa’s village began to attend to her, Aunor’s fanbase was largely composed of young women in the height of ‘Noramania’. Elevated but still espousing familiarity with her everydayness, activism, and humility—not divine, but medium. She’s bakya, unusual—because she is Filipino, and Filipinos who look Filipino cannot appear to be stars. But the network has been re-coded, there is a new alternative to being. She’s Ate Guy, referenced as familially as we refer to the Mother Mary. In one excerpt, Aunor reflects on her fanbase, it almost sounds like mourning: “My fans are no longer what they used to be but they remain loyal. There are those who simply got married, had children but when my name is mentioned, they still remember.” Devotion carries, people put faith in new things. If women have long played healing roles in Filipino folk faith and mysticism, I’d like to imagine a world where stardom reflects this restorative role, one of consolation rather than excess, one of the masses as consumed by them. But Elsa/Nora gives her body and presence, a weakly-drawn line between idol and healer that becomes a relinquishing of the self as this subject that may service all—this becomes her ultimate heresy, but also her at her holiest.

There is no Nora Aunor film that does not script her ‘own’ life. That script, as others have pointed out, invariably resolves the mythical suffering of the babaeng martir through some escapist fantasy or religious, almost superstitious, belief.

Neferti Tadiar, The Heretical Potential of Nora Aunor’s Star Power

A week before she was offered to star in Himala, Nora Aunor sees Mary in a dream. In this sleepscape, she’s somewhere in a church, and she sees the mother. “Ang natatandaan ko ‘lang ang sabihin sa mga tao na ‘wag silang makalimot magdasal.” Elsa reports seeing the Virgin Mary up a hillside. Marian apparitions largely manifest to women. She never fails to credit Christ for her successes; every other interview answer deflects to the lord. Sometimes, it is hard to read when the divine is invoked as an everyday subject that you might reach–if you pray enough–or if it means, wait for a miracle. With her, you’d believe the former: she is familiar, just us, arousing identification and succumbing to all’s need for self-identification.

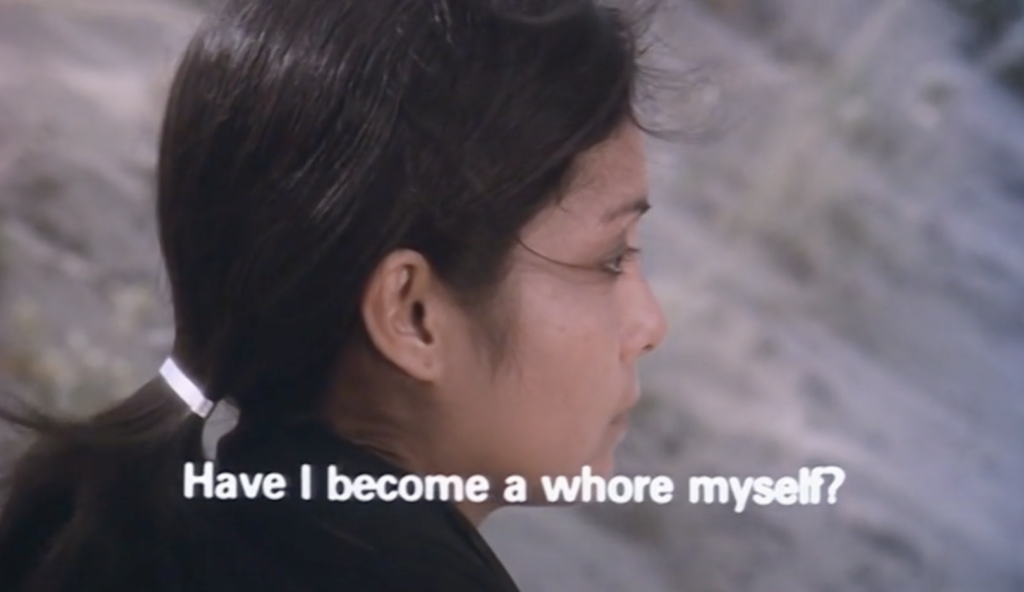

Nora Aunor is not a sex symbol as other stars of her era might be called, but she certainly becomes the same type of subject anyway. “Acting through her eyes”, staring blankly, stoic and smooth, waiting to be enveloped, for us to fill her. She is amenable to it all, a being of solitude waiting to be riled by the higher things. The self becomes an instrument of relief, as Neferti Tadiar describes in her seminal text about Aunor’s heretical and miracular potential. She is invented.

For a while, she was close to letting us see through her eyes. The “Greatest Performance” saw Aunor directing, producing, writing, and starring in a dark cinema about stardom that spun around her life’s many fictions. She sings in its opening, is surrounded by obsession, men, and provides comfort to the poorest of her fans – it’s questionable whether they’re looking at her for her, or because looking is just the human thing to do. After the project‘s rejection at a festival for its themes, she suspended the project, banned its circulation, and the material deteriorated.

In Himala, Elsa debates, “saan ka naniniwala?”, she asks the filmmaker. “Ang kamera, gawa lang niyan ng Diyos, gaya ng tao yan.” She’s always looking through the screen at herself.

A WOUNDING

Elsa bleeds. She is not untouchable like the idols. Softness is a result of sacrifice, of a necessary roughness. Did she open these wounds herself? Was this mortification just an unconscious doing? Is anyone interested in curing her? Elsa sees. Mary is outfitted in a mantle of blue, her arms are outstretched, with a wound in her chest. In the first lights after her sighting, Elsa professes what she saw to her mother, who then has her cleansed. She’s on her stomach as they whip her, bleeding and heaving, but they say the spirit cannot be taken from her. Wounding will drive out evil; in this ritual, we harm the evil thing, not the person—but malevolence always transfers to its container. It is only in the next time we see Elsa wounded by a ‘miracle’, the marks bled unto her by the divine rather than man, that delusion is slowly given credence.

The town friar condones the revelations, warning of what it means to blind ourselves. People fear a woman unleashed, from Judiel Nieva to the Mountain of Salvation. When women assume roles as visionaries, it harks back to the era of babaylans (paid labor, as Elsa receives), where Catholicism today is merged with animist and folk practices, contrasting the patriarchal church of today that is not done discoursing over Mary’s image. Contemporarily, it’s girl intelligence, a sensing and percepting that is so inhuman that it must be rendered as divine. Drought and rain might also suggest greater forces at play, atmospheric conditions that are out of man’s reach, strung along by the hand of god, catalyzing Elsa’s practices.

When Elsa is shot at the film’s climax, taking the bullet into her chest. Her heart is suggested to hold the same gape that her vision of Mary had, prophesizing her own death. Right after this declaration, she “is irrevocably converted into an image without self or body”. Killing the girl preserves this image, suspending her in this role as intercessor where all may channel their own ailments or woes as she receives no redemption of her own. In the aftermath, she is branded a heretic—her body still subject to conquest and subjugation beyond breath. Her body and her very soul have been taken, she is a mere container, as she always has been.

Belief takes credit for the killing. The director’s proof of her assault may have afforded her salvation at the cost of the sanctity of her image (and we can’t ignore how this model of ‘truth’ was only captured by him watching her viciously violated, refusing to intervene), the people’s abandon once disease was too grave for mere belief to restore (is God not here, if there is sickness and suffering? if our faith alone does not call upon him?), or the loss of her own body’s sanctity (the pregnancy in her, life after death resulting from the ultimate overtaking of her masked as something holy, how sickening it is). Seeing is a fallible thing, faith is belief without images or comprehension. Perhaps it is in this desire for legibility that our bodies are compressed into subjects for violence; only after domination do we realize people’s desires.

Apparitions elude “seeing” as we know it. The divine is briefly glitched into humanity, “the miracle appears only to disappear again”. For female visionaries, any spiritual perception demands substantiation with corporeal evidence. (Majority of stigmatists are women.) It is an undesirable position for the visionary where utmost belief then leads to scorn from others, a branding of one’s senses and soul as inhuman or corrupted. God and Mary, forces beyond normal human affairs, meddling with the spirit and human systems of comprehension. The touching gets so intense she bleeds, stigmata is cybersex as Bogna Konior declares. But as Elsa later declares, there was no external force, the apparition had originated from her; the desire is technological, and the body is some cyborgian mess. Her bloodying is seductive. It is almost erotic; her look of rawness and ecstasy upon seeing the Virgin Mary is one of ultimate pleasure, release. This is the business of selling miracles, of whoring your body for divine grace.

Bodily suffering becomes prerequisite to faith, whether sourced from divine, other, or self. Easter in the Philippines is marked by crucifixion, self-flagellation, and other punishing forms of penance, despite decrial from the church. “I will not stop this for as long as I am alive, because this is what gives me life.” Elsa’s body becomes a text of pain as her private revelation is transformed into private spectacle, her mutilation is the affirmation of the miraculous. Pleasure is derived from this suffering—Elsa finds it in herself, and others find it in her body. Theologically of course, it is Mary who appears and Christ who carries the wounds. No longer is Elsa just an intercessor: she has collapsed the distance between the domestic and the divine. She has become Christ-like herself, bearing his wounds and his outstretched arms; as the ultimate ‘vessel’, she not only carries the Virgin’s tears, she suffers as Christ does. Turned from passive, Virgin receptacle into active preacher and performer, she is simultaneously empowered and exploited. People strike the nails into her, bore the unwanted child, take her life and the heart with it. The greatest way to achieve spirituality is to carry people’s suffering. Only when Elsa dies, reassuming the position of Christ, does she become the passive, Virgin receptacle ones more. The reward for her devotion is all this brutality.

It is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives within me.

Galatians 2:20

Her affection for mirrors, screens, cameras, lenses and other looking glasses – along with her affinity with sparkles, flashes, glints, and flares — equips her with a dazzling and hypervisible camouflage – an ability to distribute herself everywhere, to hide inside copies of her own image, to peek out and observe how she is being seen so that she can reassemble herself with agility.

Alex Quicho, Girl Intelligence

In Girl Intelligence, Alex Quicho describes the Girl in a way that feels akin to Aunor’s stardom and idolatry: After all, the flash of the camera might appear indistinguishable from the apparitional appearances of Mary often cloaked in this lightness, who might be both material and wounded, transcendent and elusive. Outside of her wounds, the camera wielded by the director provides the only other testament to “truth” in the film. He’s non believing, but here the camera is his god. Elsa’s rape is a revelation itself carried by the camera, documented by a man who initially refuses to use this image to save her. So much does technology intercede on belief that it warps our understanding of the miraculous: distortions of light on Polaroid are seen as the Virgin Mary, appearing in streaks and blotches for pilgrims at Bayside. Media exacerbates religious phenomena, even conceiving of them. But Elsa/Aunor were enigmatic even before her capturing. Aunor, graced by her humility and softness, and Elsa, admired for his silent strangeness and starkness, are both networks in themselves. Noranian figures are relatable, malleable, yet always the victim of sexual violation and excess: whether holy or star (or maybe they are the same thing), she is always ravaged, never exempt for carnality, the ideal subject of dominion. Martyr, idol, saint, Virgin, all in one.

A TRANSLUCENCY

I have a different image of Jesus Christ which is that of a woman, a very ordinary-looking Filipino woman, who drinks with them and has stories to tell.

Emmanuel Garibay

Elsa, Aunor, and Mary might embody a trinity of translucency. Recursing upon these systems of feminine mediation, each one is only affirmed at its highest potential through the other, visible towards each other, enfleshing one another. Mary appears to Elsa, Elsa channels Mary, Aunor performs Elsa; but also, Aunor is indistinguishable as Elsa, Elsa transcends Mary, and Mary sculpts Aunor as a vessel.

Networks demand translucency; absence fosters each figure’s desire. In controlling the spectacle of their apparating and disappearing, these women must simultaneously be everywhere and nowhere, mortal and sacred, seductive and virgin, Filipino and attractive, empty and containing. “Her cyclical death and reappearance, her ability to mutate inside the skin of an instantly recognisable form.” To become a vessel, we must be translucent: sight at the edge of vision; vesselhood demands that we become absent & malleable enough to channel all desire beyond herself. Aunor illuminates but also obscures every role she’s in, now inseparable from the imaginary around her; Elsa becomes visible through her agony and consequent healing (so much that she is accused of wanting the attention, sexualizing herself); and Mary has always been the mediator of and as paradox. The labor of womanhood is of losing. Mary models the purity that Elsa/Aunor/we might all aspire towards—a model only possible if we become inhuman, requiring that something beyond us intervenes, where our becoming requires divine intervention.

( Think of the eclipse again. In the beginning, shrouded in the darkness, at her most opaque, Elsa’s eyes glimmered of pure bliss as the revelation of Mary came unto her. As light came again, the moon coming away, a face tinged with sadness and fear — the world has become clear again, but she must cloud this light. )

Look at the climax, the end of all ecstasy, the ending of the end. “Walang himala! Ang himala ay nasa puso ng tao. […] Tayo ang gumagawa ng himala” There are no miracles. Miracles are in our hearts… We make the miracles themselves. While many read this as a declaration of fraud, the ultimate divulgence of Elsa’s conceit, the miracle still exists within the human; it is solely too much for Elsa to bear. The so-called ‘miracle’ of her pregnancy is implanted within her by the violence of man; there is no denial of God Himself, but the denial of the origins of these miracles—of which the ferocity, abuse, sickness, and desperation comes from and is cured by mortal upon mortal. Reshaping the narrative of ‘divine intervention’, the feminine trio has become inhuman, ingrained with the mantle that was once credited only to God. Spiritual agency has been redistributed, just as babaylans mediated with the world of souls by manipulating nature. It is in this clearance that she has become undeniably crystalline, each woman frozen and canonized and theorized upon and devoured. Flesh has limits, but now that we are more-than-human, we can transcend. In her last breaths, her hand above her breast has made her, she breathes and dies in front of the lights – incessant flashes watch the wounds course through, and no one attempts to save the savior. Camera beams cloak her again, fixing her in everyone’s eyes. A hint of ecstacy. As her lifeless body lay cruciform, she has become as Christ, divine.

Miracle economies are transfixed upon and captured by the female interface. Every system that women sustain demands that they be devoured. The only way to transcend is to find the inhuman panging within the feminine body. Networks feed upon disappearance, recover after their dislocation, are to be interfered with and tampered— they prove that faith manifests most when it is distributed, deluded, and at the verge of dissolution. Every century meets new martyrs and stars, more mediators who collapse identification and allow their vulnerability to coalesce them into something beyond. Girls are all networks, inhuman channels and conduits that transcend as they become translucent, delusion is her language. Embodying the carnality and sensuality that everyone wants: to become a star, to be purified, to empty themselves into someone, to cry out, to be saved.

After Nora Aunor’s passing, I can’t help but hear all this talk about her legacy in the words of Mary. It’s beautiful to hear of a life described as a meeting point, to evoke a believing of a beyond for those across class lines, to carry around with her this imagination that provokes this infinitely reproducible yet irreducibly mysterious body. I’m looking at her lost films, the shimmer of her eyes beguiling every lens, this modesty against everything. What is the consequence of Himala? Still, women are exploited, stardom continues to victimize, the church’s progressivism and position is questioned, and Aunor herself has become canonized. If the divine can be discovered within the body, then divine intervention has never been separate from human action; there is no salvation that doesn’t require our participation.

“So no, there are no miracles. Only women who refuse to disappear.”

- Himala (1982), Ishmael Bernal

https://archive.org/details/himala-1982 - Documenting the Divine, Chia Amisola

https://www.are.na/editorial/documenting-the-divine - Forum Kritika: On Nora Aunor and the Philippine Star System, Joel David (h/t @sinefiles)

https://archium.ateneo.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1652&context=kk - The Noranian Imaginary, Neferti X. M. Tadiar https://archive.org/details/isbn_9789715503587/page/60/mode/2up

- ‘Himala’ Review: The Evils of Blind Faith and Fanaticism

https://www.sinegang.ph/filmreviews/himala-1982-lm - Girl Intelligence, Alex Quicho

https://aksioma.org/girl-intelligence - Bogna Konior: Determination from the Outside: Stigmata, Teledildonics and Remote Cybersex

https://sumrevija.si/en/bogna-konior-determination-from-the-outside-stigmata-teledildonics-and-remote-cybersex-sum12/ - Nora Aunor was Queen of ‘Bakya’ (A Requiem), Resty S. Odon

https://www.facebook.com/Resty0907/posts/pfbid0aut2YvPtsU1GuDFz8YeUVZJTwm5VobKNGC5vcx3gqSKg7QrZuEMtp8ti2kETtshgl/ - Faith, love, time and Nora Aunor

https://verafiles.org/articles/faith-love-time-and-nora-aunor - Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl, Tiqqun

- Mother Figured: Marian Apparitions and the Making of a Filipino Universal, Deirdre de la Cruz

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/M/bo22053864.html - Fall of Grace: Nora Aunor as Cinema, Patrick D. Flores

- The Impersonal Within Us: A conversation with Bogna Konior

https://www.chaosmotics.com/en/featured/the-impersonal-within-us - Acquiring Eyes: Philippine Visuality, Nationalist Struggle, and the World-Media System, Jonathan Beller

- Heretical Computing, Alexander Galloway

https://icamiami.org/video/alexander-galloway-heretical-computing/ - Cult Fiction: Himala and Bakya Temporality, Bliss Cua Lim

- Acute Melancholia and Other Essays, Amy Hollywood

- The Word Made Fresh: Mystical Encounter and the New Weird Divine, Elvia Wilk

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/92/205298/the-word-made-fresh-mystical-encounter-and-the-new-weird-divine/