I write this a few weeks after I’ve finished my first year of college. I broke and lost lots of things while moving out, and gained a lot more footing in reality after realizing how much of me can be tucked away in boxes–practically compartmentalized in medium-sized luggages. There is a repeating image of me, airport to airport, staring at rows of Smarte Cartes and wondering if it’s worth spending six dollars to save myself some back pain. (It never is.) I can’t express how much I’ve changed in the span of a year, and the gravity of this change alone is something I have trouble comprehending. Last year, around this time in 2018 I was traveling to America doing nothing surrounded by family: was so frightened and scared into my decision of choosing my current college over Dartmouth that I never replied to my admission offer, caused a war in a one-bedroom apartment occupied by a near-dozen people because I wanted to go to a shitty, local record store on my birthday (I picked up my Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas to Heaven vinyl there), spent three weeks in America doing nothing. In the past year I’ve been in America more than I have been home, wandering aimlessly from New York to New Jersey to San Francisco to Los Angeles doing everything, but alone. My worldview on everything has drastically shifted. I feel I use myself and other people differently now, but am no less manipulative than I was one year ago — not that I ever was good at it. I can’t read huge blocks of text or spend time pouring over long threads, which is something I’m trying to reverse but frequently regret doing since I realize I learned nothing at all. I can talk over the phone but I still need some preparation and can only do so for career-related things, I can be perfectly content with being alone, I can’t hold conversations in-person and am pained if I don’t get to talk about something that interests me or something that I make with others, I think nothing in particular is as painful as undoing all of this.

I want to tell you that my first year of college has changed me dramatically. When my friends back home ask me what it feels like to be thousands of miles away, I offer nothing but complaints and give them the impression that school in the United States is nothing but an overglorified fantasy — but it’s really not that overglorified, I think. There’s no way for me to be able to express how much everything is, and how I’m still having trouble taking it in. There’s change that I can’t articulate, nor do I have any lists for or stories. It’s this deep, fucked transformation that makes me afraid to be reflective; because it’s something that has yet to settle.

My friend worded that nineteen is kind of the year when we’re fucked. Lorde has made no music describing the feel of anything past; Boyhood ends on the note of mushroom-induced, teen pretentiousness in college freshman year. Personally, I made it a note to swear to achieve a slot on Forbes 30 under 30 as a teenager (because all your achievements become significantly less impressive when you lose the -teen moniker), and given my nonappearance in this year’s Asia list – I’m falling significantly behind. I still get anxiety when I talk to people, and just spent four hours of my night having a crisis while contemplating posting myself on /r/amiugly; this is something not so different from when I was thirteen, naive, and scared of the world.

Listen: nothing is remarkedly different. I make fun of Silicon Valley tech bros and people who listen to IDLES, but I will still likely date one (either of the two personas I enumerated, but preferably a mix of the two) and almost wore my “Idles Brutalist Socialist Club” shirt out today. This is the college computer science major equivalent to who I was in middle school: thinking I’m better than everyone else because I listened to Pedro the Lion instead of Hillsong, making fun of the English majors who smoke Camels and the Economics people (according to Facebook meme groups such as “Amazon Presents: Elitist Memes for Ivy League Teens“, they’re referred to as “snakes”; I should use this term to make this droning essay more relatable so that people can actually recognize some of these jokes but that’s not up my alley). It sometimes feel as the dramatically forced directional shift in my life has done nothing but force me to reroute familiar experiences, replacing Rustan’s department stores with Macy’s with the only forced exchanged of having to treat service workers with a lot more humanity than I’m used to.

Growing up with this affirmation that I’m as naive and impressionable as I was back then is scary. Because I had room to grow back then, and it was more acceptable for a token Catholic school sad girl to be confused and hate herself. But now I have a LinkedIn nearing 500+ connections and still go through my Twitter feed liking a lot of activist-driven rants about political theory that I’m only half-assing, liking something until somebody else tells me that’s bad and going “oh” until someone tells me that that take was bad and going “oh” fully affirming my lack of mental independence until now. My Philosophy T.A. also pushes this in the academic setting, blessing me with a remarkable “just a third of a grade below the class average” grade of C+ as I blabber about my home country in ways she thinks is interesting (potentially a spot of pity, to show that her 3-sentence response to my 3,000 word behemoth is not all overt “god you fucking suck”) but really not because the goal of the paper was not to be critical or offer any new insights but be very surface-level about the readings regurgitating what we had discussed in the sections I only attended half of. Now if I’m unsure of what I stand for at any given moment, it seems like my worth as a person is inherently deducted. Now I bear this implicit weight being an international scholar from a country I miss and can’t stop missing, the only one of four in my year at a prestigious foreign school, while not understanding the white language of my philosophy readings and still being uncertain about politics – much less that of America’s.

Manila’s sky is often so blistering that I don’t recall looking at it often. I know, though, the clouds are thick and wispy at the edges – the kind you see in stock photos. Closer, at sunset, I see this image in beaches with mountains and roads at their turnstiles, steep and diving and clashing with the humid air. They’re left as thin strips, wavering and almost never there.

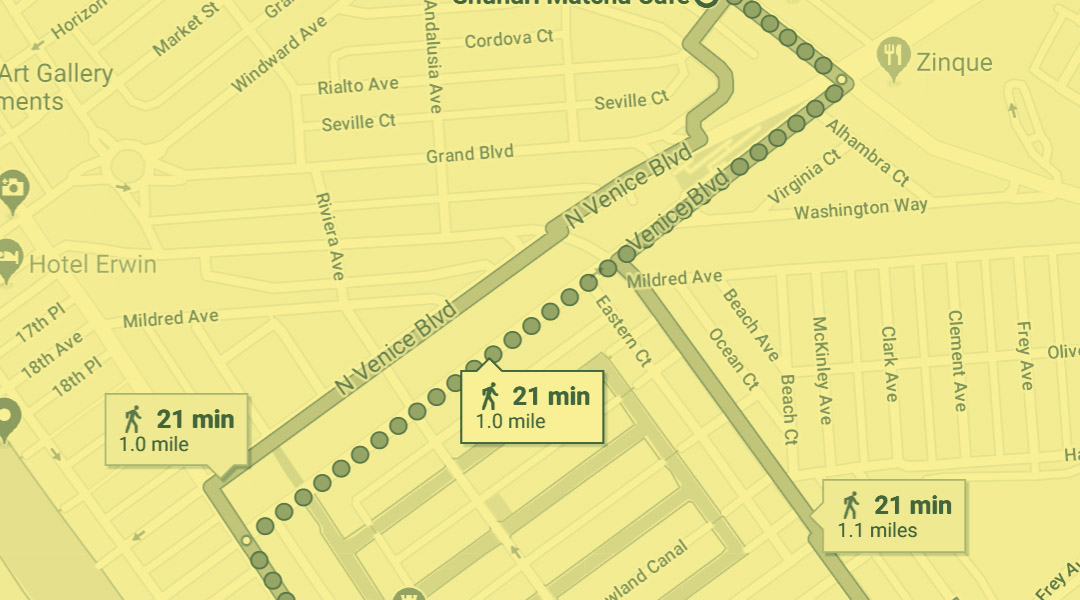

Skies in Connecticut are grey and unbowing. Winter is a lot less worse than I thought it would be, but also a lot longer than I expected. Sort of like how my mental illness has reimagined itself into long-term dysthymia, if you will. My favorite spot during freshman year, I tell people, would be the Yale University Art Gallery. I held a job working for it (but not in the main building, alas) during the Spring semester, and I’m proud to say that it has a beautiful contemporary art collection and a nice courtyard. (Across it is a British Art Museum which I have never stepped foot in, yet.) I say these interesting factoids: it’s just a three-minute walk from my dorm room and I go there to destress, which is false because they closed the High Street gate next to Linsly-Chittenden around mid-Fall which has made it a five-minute walk. It’s open late on Thursdays, and I love the programs there. (I have not attended one, but I did attend a film screening once.) The true answer is that my favorite place on-campus is the Starbucks on Chapel Street, especially at 5am on opening days — and best during the winter. There’s an instant intimacy about being there first thing, a desperate connection between graduate students, residents, passerby, and all. In the dead of the morning I’ve felt like the only noise; arguing with everyone, staring into my phone before making the conscious decision to skip class as I walk over to pick up another matcha latte, become someone distraught over the six-day drought of matcha powder. The last thing I did before heading to Union Station on move-out day was stop by, and call my last Uber from the school year there — a backpack and two totes strung over me, plastic carrying four too many vinyls leaning on a carry-on luggage, the driver sharing a “shit” after shoving the biggest trolley in the back of his car, quickly running to rearrange things in one of the last New Haven suns on the corner of Chapel and another street I never learned the name of.

My life here could be measured in shopping malls and department stores. Manila routine is going to school, going home, and maybe going out every few weeks or so. On some weekends, the way I glimpsed the world and slipped out of my sheltered place came from these trips to malls. Never riding the ferris wheel along the boardwalk along Mall of Asia, stepping into the church beside people sleeping along stalls selling fishballs and parking lots to find a bathroom while running out of a line wrapping three times around the convention center, losing a polaroid photo on the steps of the arena after a concert at fourteen. I walk across the heat of Alabang on familiar tiles, places I haven’t stepped in since being eight, no longer having to surrender my bag at a shrinking Fully Booked.

When I arrived home, the second place we went to was the mall. (The church, then it.) Wading through wings and shining tiles, I thought about the pace of the Filipino life. Never mind the silence, the inability to confront in all these people, but the passive and all that follows. There’s no intention in the way people here walk. There’s no need to justify why we are, and where we have to go; a sore change from the urgency in metro lines and the gaze to let someone know that I’m here in century-old buildings. As we walk, we exchange the same diluted conversations: a new place here, where old people are now, money as a constant chaser.

Returning back home I know there is nothing grand. On the fifth day my luggages still line the floor of my room, and the spaces in front of my closet strewn with clothes I’ve never worn since being twelve. Even after a year away, I find all my old habits return instantaneously: there is no reason to be friendly, or even kind here in a space where everyone treats me as an enemy; there is no genuine word for respect in the Filipino tongue and this heat has taught me that I can only walk away; ingrained lessons. Don’t flush the toilet until you absolutely have to, bathe only by soaping your body and rinsing off the surface, walk over plastic bags and shopping bags and know that you do not need to exchange any works to the service workers. Compare prices, costs, and pretend you know all the people you meet.

Manila does not care about my education, personality, or what I dream about. When I come home, everything I have proven to anyone but myself is taken away, and it is like renewal. There is nothing I can say or offer or anything that I really am willing to do anymore: listening to the faces of people I no longer know and perhaps never truly knew makes me realize that there is a leaving story here, finding that the bounds of where we came from are sometimes the most destructive things.

But these are bad things to say. Living isolated from the Philippines has done more wrong than good, and it’s probably just the initial shock of returning to all the old values that I have worked hard to erase. Greetings extend to surface value banalities (things masked as you look so bad now) that I almost would prefer white people at parties asking me how my English is so good. Sometimes, I do. In fifteen seconds you become a bit more understanding of comment sections and the tired, enlightened middle-class letting down their guard and saying there is nothing left that they can do for this country as they blame the people for never willing to be educated. And in the moment, when you see someone talk about how they’re going blind and left to find work for eight sons-and-daughters with how they greet you and never learned anything it’s almost like you understand the word about leaving. And it’s easy to say you love a country when you only say it when you’re no longer immersed in it: beyond skyways and telling yourself three-hour commutes for work you’ll never leave a dent in will mean anything to this universe, trying to find some form of justification for why I still have this meaningless, dainty dream.

I’m a child again here. And when I’m here, I always will be. There is no explaining how hard it is ingrained in me to hate the sound of doors opening and closing in my own home, or how each and every knock (if ever there is one) takes me back to meaningless repetition in high school or fistfights to the head. Nothing I can do will stop these memories or make this country understand me.

Sleeping in my bed (a mattress on the floor) and tucking myself over piles of clothes unwashed for years, asking for water like sin, finding these granular bits and pieces of a younger me and discarding everything. No one asks about what it’s like to be away for a year because all they can think about how great it must have been. No one will ever hear about what was good, because this country teaches me to say only the worst things about where my life is going: I need to convince them underneath the supermall lights that my existence and wherever I am going is a mistake and that the work I do is a blur and that I will fall again into the same promises unmade of me when I was young: be enough, eat only consecrated bread on Sundays, and say nothing back.

As I write this, I find that I’m going through all the nauseating emotions that being alone countries away allowed me to unlearn. I’ve slammed my fist down on my glass desk a dozen of times before ten in the morning – because this personal assault is the only way I know how to deal with anything here. It’s as if suddenly I understand why the lack of intervention had made me grow so much, and why I was pained by anyone back home. I can now articulate, I feel, what exactly in me has changed a bit more clearly; these are the same things that people pick at me for when I’m no longer smiling and picking up myself in the counter with more breaths than necessary, when I walk faster and faster and faster in a sea of people who wait aimlessly until they can predicate themselves on anything they perceive to be smaller, why the shift in voice and tone is signatory of fear more than my own experience. Because speaking louder and noticing the smallest of things to allow my own voice to fill all the space in the room is not what I am meant to be taught, or what I would be allowed to.

Because I’ve fucked myself over in the dead of the night in the most unsafe streets in a country away. Because I’ve learned to wash, dry, cook, burn, save, salvage, and push into boxes in ten months what I was meant to in eighteen years. Because I piss without stumbling in front of seven other people and boil my own water to share and not to keep. Because I left this country knowing that I would never be happy and return knowing that those words were put in me to prevent myself from being what I could be.

But you couldn’t believe that from the few pictures I took. (Never got to finish a single roll of film.)

When I arrived at the airport terminal to California, I heard the first breath of Tagalog spoken, in person — not just on shitty Facebook videos, if you’d believe in — the first that I’ve heard in months. Suddenly waiting an hour going on two next to a tired mom, lola, and a young girl chewing off a Hello Panda packet and swinging in the domestic arrivals section of LAX was the most comforting thing in the world. I caught myself carefully listening for the little tidbits: the na, the same way I listen to myself – stumbling and never able to speak straight while leaving conversations half-fulfilled.

Everyone wants to write a book. None of my writing here will mean anything unless it’s in some sort of novel form. That’s the thing about words. I could leave them littoral, far away from the spaces I choose to let myself be in. Nobody believes in what you have unless they come with leaflets and loose words. In high school, I was the girl who said I was writing a novel. I let it live and die in a Microsoft Word document, accessed only by a .edu email I can never really get into anymore. Whenever I tried to write, my laptop would crash — or come close to it. The entire story never really left that space. I did not talk about what I was writing, nor did I ever take time to plot out what was happening or why. I sat down in long stretches of time, beginning conjectures and applauding my senior year self for writing witty, intellectual deliveries about the world around me. I did not know a thing about the world. The protagonist in the novel, of course, was me. Everyone was nameless as I chose to refer to people solely with pronouns; a choice that was pretentious and disastrous, but featherweight with how there were really only three people in the story. My biggest feat was the personification of the world into two divisive characters and myself: a telling sign to how I viewed things, and maybe even continue to view them.

I never finished the book. Never either, did I scroll back up and understand where I was in the story. I wrote about highways and looked up the composition of lakes: I wrote about women and men and young girls in bedrooms and their thoughts because it was all I could write about that would make someone feel; I can’t tell you deep things about the sky or come up with seamless dialogue that doesn’t hurt a little bit. You can’t make me write stories when I don’t know how to tell the one I’m in, at the moment. There’s no reason either to finish the novel when its useless: there’s no power to words, I’m losing the edge of being able to sell what I make in my teenage years before I lose out on the already dwindling interest in my selfhood, and I want to leave the banks of my youth in places more concealed, like this blog. There’s a story to be found here, too. It fascinates me because I can keep writing and writing, and nobody will read this until I’m dead or something great happens — and the extraneous never come here. This is my novel, perhaps.

There are no words left for the feelings here. I want to make something big. I want to be the star of it. I want to feel like I can put myself into something nice, brace myself for the overwhelming realization that I am alone in everything I do — but perhaps not without the comfort of words.

Last night, I dreamed of myself as immensely mine. Along the Library of Babel, strewn room to room with all my selfhood and orifices stripped for patronage and pilgrimage: I imagined writing over the letters, making sense of things, and penning the words down. There is no use in searching if the answers could be here, with me. And in the sunless dust I looked over at the finitely bouncing reflections and wondered what man could be in a universe where we are left with time only to think: then I caught myself falling downwards in this world that we cannot yet truly illustrate, like my chest evaporating with my hands slowly going numb as I looked up into the endless things that we could never unread. And then I knew. And then I woke and sought to see.