Sharing a copy of this writeup (another long anime essay) I wrote on the 27th for my site. The full, annotated, and most updated version is part of the Khaenri’ah Lore Project library and can be found in this document. For being written in a few hours, I’m pretty proud of it! It helps that these put together thoughts and bits of evidence I’ve had for a long while.

Like everything else under this side project, it won’t make sense if you do not play Genshin Impact…

Warning: Uses lines from Inazuma Archon Quest Act I, Inazuma talent books

Disclaimer: I’m noob to Confucian theology (not that it’s a huge point here), not 100% sure about the Chinese so pls feel free to correct. <3

Visions and ideals. You’ve probably read about and speculated about this yourself. Each Archon stands for their own ideal, from Venti’s love of freedom as a loafing bard, to the Tsaritsa’s calculating approach to ‘love’ (as speculated by Dainseif’s introduction of her in the Travails).

Pyro is passionate. Anemos have dead friends. Geo is determined. But we’re thinking about this in the completely wrong way.

This is a post about Visions, why most ‘Vision discourse’ about character trait/ideal connections is fruitless, what I think they get wrong, and a new theory on ways to think about ambition, ideals, and the heavenly principles.

The issue with Vision discourse

Most discussions go like this:

A: Hydro is about connection to the divine. Mona’s divination, Barbara as a deaconess, Childe and his servitude to the Tsaritsa, and Xingqiu continuing the Guhua clan’s arts (who later ascended to Celestia), Kokomi and her god’s legacy.

B: Aren’t some of those stretches?

A: No, because…

or

B: Couldn’t it also be about dedication? Or about the mastery of their art?

A: Well yes, but…

or

B: Hey, what about Hu Tao? She’s continuing the Rite of Homa (or the modern version of it), the practices of Wangsheng, protects the border between life and death stricter than others, and essentially deals with the death of gods and adepti. You could even include her fame for poetry, and her reference to mortality against divinity.

A: Hu Tao could never be Hydro. Because…

Or any other variant you can think of. It’s fun to come up with these interpretations, but discourse often goes around in circles. But…

1. We simply don’t know enough

Hopefully to be addressed in the rest of the Archon Quests, Visions have simply been left vague. What little we know of Visions can be summarized as this:

- Visions are external magical foci given to mortals as recognition from the gods, allowing them to channel elemental power. Vision bearers are called allogenes.

(Traveler’s Vision Story & Venti in Ending Note)

No one knows how they’re given.

Some characters believe that their regional Archon grants Visions, regardless of element. Klee’s ‘About the Vision’ voiceline thanks Barbatos’ for her Pyro Vision: “This little marble is supposed to be a present from Barbatos to say well done?”. Keqing also credits Rex Lapis for her Electro one.

Conversely, Baal was able to restrict Electro Visions. In Act II’s Prologue, Kazuha speculates that the Seven Archons each have their own criteria for granting Visions. In Endless Research, Alrani, a scholar from Sumeru Academia suggests that the lack of Electro Visions is due to “the will of the Electro Archon”. Archons may have some degree of influence, but it being due to their ‘will’ remains unconfirmed.

The Traveler’s Vision story tells us this:

“Celestia is the realm of the gods, and the wielders of Visions walk the earth below. When they depart from this world, the chosen will ascend.”

…and Xiao’s:

But do adepti receive their Visions as a form of acknowledgment from Celestia, like humans do?

Note how these lines emphasize Celestia. This suggests that those in this abode have more influence than what commonfolk or even allogenes may think, especially given that they mostly attribute Visions to the Archons rather than any higher gods (Xiangling’s “I think the Archons agree with my passion, or else they wouldn’t have given me this Vision”, Beidou’s “those with Visions are like flagships from the Archons to follow”, or Amber’s “My Vision… Is a sign that the Archons believe in me.”). It could also mean that Archons are simply the last line of ‘approval’.

Mona’s story does remind us: “The gods, too, are bound by the rules of this world.”

…

I don’t want to think about Vision casing. That’s a mess.

2. Visions are connected to ambition or desire, weaker than ideals

With so much ambiguity on how Visions operate, we’re left to extrapolate meaning from characters as unaware as we are (voicelines, quest dialogue) and our relatively objective source of truth: the Vision Story.

Here, Visions are constantly referred to as a sign of recognition, favor, or witness.

- Diluc: “…a Vision is simply an extension of their strength, a medium for channeling their willpower, a tribute to the experiences that have shaped them, and a testament to the story of their life so far.”

- Ganyu: “Her Vision, then, was proof and witness of her new duty.”

- Bennett: “Getting recognized by the gods…”

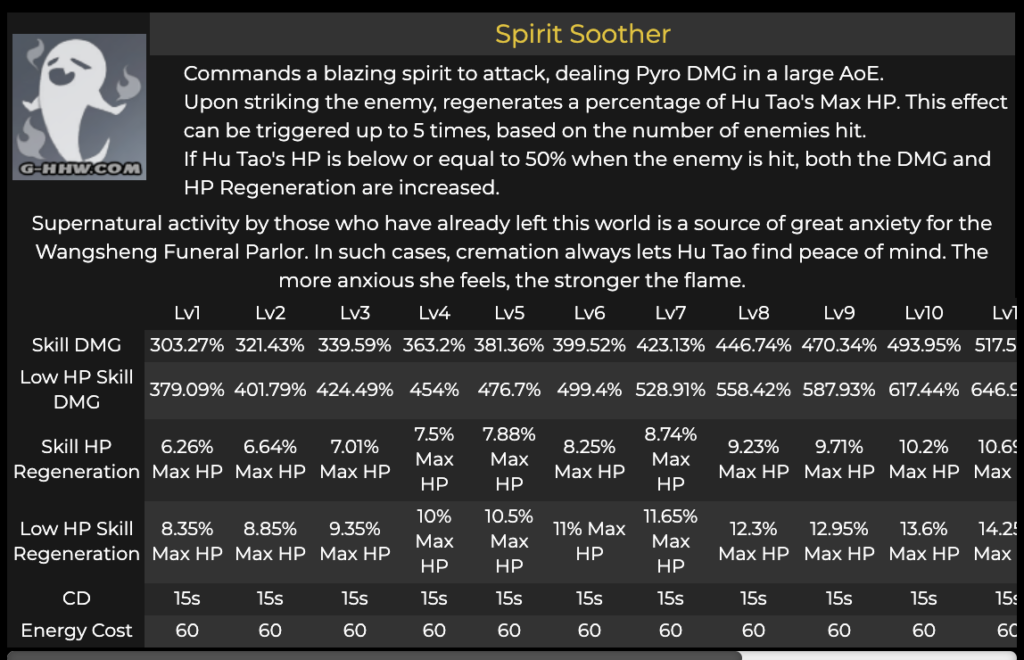

- Hu Tao: “…the ultimate recognition of her strength.”

- Rosaria: “It witnesses me, and I witness it, that’s all.”

- Mona: “The people of this world consider [Visions] to be a sign of divine favor and the source of all power…”

- Chongyun: “…earned him the gods’ favor…”

And Visions themselves represent and come from desire and ambition. In CN this is 願望, which is ‘wish’ or ‘yearning’. While ‘ambition’ is used consistently here and in the theory, they’re closer to desire in the source text.

Even more ‘objective’ sources, like Character Story narration (as opposed to character voiceovers) use this consistently:

- Qiqi: “…a desire to protect the past”

- Barbara: “Everyone has their own desires. To bring together and fulfill those desires and make everyone happy – this is the purpose my Archon has bestowed upon me.”

- Ayaka: “Visions are a seal of approval for those who are the most ambitious.”

- Diluc: “…he took it as recognition by the gods of his and his father’s shared ambition…”

- Yanfei: “Visions appear in response to strong desire…”

- Kazuha: “It symbolizes the mortal desire to always keep moving forward…”

- Xiao (an adeptus) literally has a line titled ‘About the Vision: Desire”; this line will be brought up again later: “Visions? Desire? Ha. Do not judge adepti by your mortal ideals. I have no desire.”

In Three Wishes, the Traveler states that touching the Thousand-Armed, Hundred-Eyed God’s statue had them hear “the sound of people’s aspirations”. Thoma says “that is where Visions come from… In other words, a person’s Vision represents their ambition.”

But ambition and desires are innately weaker than ideals.

An ideal is an apex of ambition or desire, a perfect standard of principles in full pursuit and precedence. Ambitions are merely yearnings, wishes, wants that require action. Visions represent ‘mortal desire’.

The intentionality of this distinction is seen in the consistent word choice between ambition (願望 or desire/wish) and ideals (理想).

Most telling is Zhongli’s recall of Baal’s fondest adage in the Fond Farewell:

EN: “Seven ideals for seven gods, and of these, Eternity is nearest unto Heaven.”

在七神追寻的七种理念中,唯有『永恒』最接近『天理』。」

Among the seven concepts pursued by the Seven Gods, only “eternity” is the closest to “the law of heaven.”

The ideal (理想) seem to be used in reference to the beliefs of Archons and gods. During the Archon War, many gods struggled for their ideals. They can perhaps be thought of as personifications of these ultimate principles.

- In Treasure Lost, Treasure Found, Soraya mentions that the God of Dust Guizhong’s ideals are still taught.

- The Varunada Lazurite Gemstone narrated by the Hydro Archon: “My ideals have no stains.” (「我的理想之内并没有一丝污浊。)

- The Divine Body from Guyun material is animated by the divine remains of lamenting gods, “they are unrealized ideals, designs for a prosperous humanity that could never be.”

This is supported by how each region’s Archon seems to take on a new ideal as the seats are changed: the previous Dendro Archon was the God of the Woods, whereas the current one is the God of Wisdom. Archons are an ideal incarnate, but only in a vacuum could these ever be perfectly maintained.

The gods themselves, including the Archons, are constantly in pursuit of their ideals, hence Zhongli’s line, “seven concepts pursued by the Seven Gods”. It’s not unfair to say that they do a much better job at adhering to these than mortals, especially at their prime, but it’s also unlikely personifications of such beliefs remain perfectly steadfast––especially as the times change. (More on this later.)

Ideals vs the Heavenly Principles

The same adage quoted by Zhongli makes specific use of 天理 Tianli when referring to the ‘law of heaven’ in CN, 天理 meaning heavenly principles or natural order. The prominence of this term is quite lost in English; in Confucianism, they are the universe’s fundamental laws, unalterable by humans. The heavens overruled human efforts, and was the “supreme source of goodness” whom gave people tasks to perform to teach them virtues and morality. e.g., a region’s welfare depends on the moral cultivation of its people, beginning from the nation’s leadership. A ruler’s sense of virtue acts as their primary prerequisite of leadership.

In Genshin Impact, each region has different relationships to gods and government––so this point treads the line between theological truth and the secular. This could explain why beings close to the highest divine are directly entrusted with the “burden of guiding humanity”, attempting to impart these virtues for their prosperity.

In the start of the game, the Unknown God introduces herself as the “Maintainer of Heavenly Principles” (天理的维系者), and the same term is used to talk about the Seven’s ideals and ploys in the Travail video:

- The God of Justice lives for the spectacle of the courtroom, seeking to judge all other gods. But even she understands one thing very well: the principles of heaven are not to be contested.

- She is a god with no love left for her people, nor do they have any left for her. Her followers hope only to be on her side when the day of her rebellion against the principles of heaven comes at last.

Our immanent (present in the material world) Archons are rulers set to guide humanity, while higher transcendental principles appear to be referred to here. Even in the context of the Seven, the “heavenly principles” are a more fundamental, higher level of order, positing the ideals of the gods/Archons below it––which adds up. Think of it as heavenly principles > ideal > mortal ambition/desire.

The Sustainer of Heavenly Principles is threatened and ‘fading away’ (as in the Traveler’s Character Details) for a reason:

EN: The keeper is fading away; the creator has not yet come.

But the world shall burn no more, for you shall ascend.CN: 维系者正在死去,创造者尚未到来。但世界不会再度灼烧, 因为你将登上 「神」 之座。

The Sustainer is dying, the creator has yet to come. But the world will not burn again, because you will ascend to the seat of 「God」.

What now when the God of Contracts has signed a contract to end all contracts himself? Or the means of Baal’s frantic, oppressive rule of eternity? If Archons themselves struggle to ensnare themselves in these concepts, what more finicky humans in a tumultuous world?

3. Visions recognize a moment’s ambition

So what then is the issue with how people interpret why mortals are favored with Visions of certain elemental types? It’s simply that this recognition can occur with any facet of one’s character: there is no singular, one desire or ambition that one can embody––they are lesser than ideals. These are fleeting, frequently imperfect characterizations of our cast––putting people together in Anemo = [trait] alone will always have flaws, which just means good writing. The gods recognize one of many desires, and this particular happens in a particular moment.

This is heavily alluded to in Chongyun’s story––which outright says that he could have easily been ‘Pyro’––questioning the goal (we can take this as similar to an ambition) in response to his Cryo Vision being given.

…Perhaps it was this resolve that earned him the gods’ favor — that said, the Vision granted to Chongyun was one of “Cryo” rather than “Pyro.”

As to which of his goals it was the Vision responded to, that is also a mystery.

It’s critical to realize that Visions seem to respond to specific moments of ambition and will. Our Traveler’s story says this explicitly:

When faced with circumstances that they cannot control, humans often bemoan their powerlessness.

But if a person is found to have surpassing ambition even as their life reaches such a desperate turning point, then the gods would look upon them with favor.

…

Is it wise to allow a moment’s ambition to dominate one’s entire life?

This ‘domination’ could refer to the reliance on Visions that bearers find themselves held to, or more abstractly, the psychological costs and trade-offs they live with.

Zhongli further stresses that Visions appear during a ‘fateful moment’ in the Fond Farewell.

But if a person shows true strength of will at a desperate and fateful moment in their life, the gods will look upon them with favour.

Could the receipt of a Vision be something written in fate, or one that changes their fate? Kun Jun mentions that ” fate is ordained by heaven”. Just as the Archons go about ruling their people in different ways, the question as to how Visions as an instrument are used by the Archons or higher gods remains.

Vision stories

Chongyun’s story is a direct questioning, and it’s wholly possible for moments of will to be unknown to us, such as for characters without revealed Vision stories.

There are three broad classifications for the ‘narratives’ present in Vision stories, helping us know how accurately we can class people––if it’s still worth it at all.

Most characters like Diona are straightforward: during a storm, she unknowingly froze over water in her path while tracking her father using her Cryo Vision. Chongyun is more ambiguous and theoretical––talking about conflict with his yang energy & exorcism career but no specific moment. Other stories have no mention at all, talk about conflict after a Vision: Childe’s is about his Delusion and Xingqiu’s on his Guhua practices after receiving the Vision.

The categories and some characters that fall under them:

- Defined (describes precise moment; answers several who/what/why/where):

Qiqi, Beidou, Hu Tao, Bennett, Barbara - Ambiguous (talks more ambiguously about traits that could have kindled Vision):

Chongyun, Xiangling, Diluc - ??? (not mentioned at all, post-Vision):

Childe, Xingqiu, Keqing (just about her trying to destroy it, vibe)

This means that it can be pretty arbitrary. So take: if Bennett or Hu Tao’s story in the third category, it would be harder to place them. Without knowledge of Bennett being seconds away from dying, or Hu Tao trekking to the border and waiting, we’d only go off their broad character––which doesn’t always give off the best guess of how they’d canonically act in some of the most pivotal moments of their life.

It could also just be a MiHoYo thing: X character sells well as Pyro/Cryo, the most desirable DPS elements, so a story is made to justify that when it could fall into any other, or that story is clumped into Pyro/Cryo.

The point about these moments is that they often happen in “fateful” circumstances beyond their control. Extremes of a human person that we can only make guesses on unless written out for us. Or convenient moments that are honed in on for plot/gameplay reasons.

As a counterpoint, we do have characters who’ve received their Visions in more ‘mundane’ moments, doing their regular tasks––nothing desperate about the moment. Perhaps it was just that in this moment that the gods finally decided to look upon them? Mona’s indwelling the teaching aid given to her by her master, Sucrose just plopping her new Vision into a cauldron on “an afternoon like any other”, Albedo giving his a single glance before carrying on with his research…

Lisa’s seemingly mundane Vision story also holds a lot of implications about her relationship with knowledge, the divine, and cost of Visions. I count this separately even if it seems similar to the other three:

“Hmm… I suppose I shall need a Vision, then.”

And just like that, as that thought popped into her mind, her Vision popped into her hand.

…

With the aid of her Vision, Lisa acquired the knowledge that she sought. But she also sensed the deep secret hidden in the shadows of that knowledge.For whatever reasons, the gods gave humans the key to changing everything, but they did not explain the cost involved. Lisa grew fearful of the truth.

The Vision that hung from her neck became to her a bottomless pit filled with sweet delights, lingering at the back of her mind.

…

If you subscribe to the theory that gods grant Visions to influence a person’s life trajectory (in similar vein to how constellations “determine the shape of one’s character” and map out Vision bearer’s destinies), then this supports that. The gods stepping in to save Bennett from death, divine recognition intervening in the crossfire that resulted in Qiqi’s mortal wounds that let the adepti breathe life back into her, Diona’s struggles with her Cryo Vision, or Keqing’s worldview about divinity changing…

“Visions… are also a type of contract. You should know that all power comes at a price. For every bit of power you gain, so too do you gain more responsibility.” Zhongli mentions. As much as people reject or try to avoid using their Visions, its influence lingers.

Such that a moment’s thought could then influence a Vision wielder’s whole life––depending on how reliant they are to the elemental focus…

4. Divine ideals should be looked at distinctly from human ideals

This point is the least strong, most subjective, and most speculative.

Earlier, we established that the Seven themselves are subject to higher heavenly principles (maintained by the Sustainer of Heavenly Principles), with roots in Confucianism. Herein Confucian theology, “God has not created man in order to neglect him, but is always with man, and sustains the order of nature and human society, by teaching rulers how to be good to secure the peace of the countries.” In realizing one’s humanity, they become one with heaven by the contemplation of the order of creation and the source of divine authority.

Similarly, in Valentinianism, gnosis is about insight into the true nature of humanity, a path of salvation leading them into celestial existence.

This distinction between man and god even operates on the level of the adepti. In Xiao’s Developer Notes, we learn that “humans have a higher purpose than adepti”; meanwhile for illuminated beasts like Xiao, an ‘inner eye’ serves as the true source of power and Visions are only worn to “comply with the expected norm.”

“Visions? Desire? Ha. Do not judge adepti by your mortal ideals. I have no desire.”

When in Xiao’s Voicelines we inquire about Visions and desire, he shrugs the Traveler off. Clearly he has his own objectives and is generally cold in his lines, but the interesting part is the measure of mortal ideals. This is close to the CN text as well, saying “don’t use mortal standards to speculate about immortals.” But, Xiao very much has mortal ideals. He longs for the “tune of the flute amidst a sea of flowers”, and almond tofu helps represent his simple, sweet dream. What does it mean when even the illuminated bear human wants? This is even more pronounced in Baal’s case, who must detach herself from earthly desire…

Coupled with the idea that mortal desire only goes so far, that Archons rule their nation with ideals they’ve enkindled even before the gnosis (assuming they were gods), and how the highest heavenly principles themselves are untouchable by man––there must be an order inherently unreachable. Our mortal cast, recognized by the divine, in reach of only so much.

In the beginning of the Travail, Dainsleif mentions this. I’d like to highlight the emphasis on ‘desire’, references to Visions and how they appear to be a doorway to divinity:

EN: The gods goad us on with the promise of their seven treasures, rewards for the worthy, the doorway to divinity. Yet buried in the depths of this world lies smoldering remains, a warning to those that dare trespass.

CN: 战争已经开始了,是上一场战争的延续。众神为欲望的轮廓镀上七种光辉,以此昭示,他们的权柄可被企及。而现世的基底埋藏着阴燃的残骸,那是对僭越者的警示…

“The goads gild the contours of desire with seven lights of radiance; by this method, you may touch their power. But the smouldering ruins buried in the deepest foundations of the world are a warning to those who trespass…

Mortal belief vs the gods

Gods stand for specific divine ideals that are laid out pretty broadly, which is why there’s so much overlap and contention in the first place. Naturally, from their ‘perfected’ ideal come philosophies and teachings that their region emulates, which are our talent books.

This section focuses less on gameplay observations (i.e. nowhere does this insinuate that talent books are actually consumed regularly to gain power, just as how we do not pick up thousands of Crimson Witch pieces in actuality), and are more concerned with the implications of their flavor text.

We do know that talent books have canonical basis, as in Yanfei’s 2021 birthday letter:

“Here, take this Guide to Prosperity. No matter where you venture off to, don’t forget what people pursue in the land of Geo.”

What people pursue. Potentially influenced by the gods’ ideals (either the original Seven or current) but still a pursuit adapted by humans later on. We have no information about the origin of books themselves. Nevertheless, these ‘teachings’, ‘guides’, and ‘philosophies’ do seem to be the work of people from each nation sharing their form, foundation, yearnings, symbols from their experiences in their region and their Archon’s method of presence.

Freedom-Sworn even questions whether a region shapes their Archon or vice-versa:

“They say that a region’s character follows that of its archon, and that this holds true both for the people and the land itself. But was it the unfettered archon who bestowed a love of freedom and wine upon the land and people amidst conflict? Or was it the people who nurtured the Anemo Archon’s love of freedom as they pined for it amid the howling wind and frost? This is a question that can no longer be answered.”

The rest of Mondstadt’s talent books go like this:

- Freedom: Freedom is the spirit of the city of wind. To sing is one such freedom. To sing on the land created by the Anemo Archon is to send your heart away with the song on the wind.

- Resistance: Resistance is the backbone of the Land of the Wind. The history of Mondstadt is one of resistances. People rose up to allow the future Mondstadt’s poetry to freely be that of the wind and be spread across the land.

- Ballad: Poetry is the soul of the Land of the Wind. Poetry is the manifestations of the desire to spread the word. Though nothing is eternal, though nothing will be the same, the wind’s poetry will still spread beyond the skies, the land, the seas, to every corner of the world.

…and so on for Liyue and Inazuma. While Mondstadt has a book for ‘Freedom’––their divine ideal––there are no ‘Contract’ or ‘Eternity’ books. Going back to Freedom-Sworn, could the land have nurtured this love for freedom instead? Barbatos, after all, was originally a formless strand of wind amongst a thousand. It was only with the people’s belief that he became what he is today.

These ‘teachings’ and ‘philosophies’ seem to vie with the Archon’s beliefs themselves, or the people’s trust in them––just as contradictions fill our Archon’s actions in the events of the story. Not every god is fit to rule. The Boreal Wolf materials tell us that Andrius deemed himself unworthy of becoming the Anemo Archon as he was unable to envision a happy life for humanity, lacking the gods’ responsibility to “love all people”.

The conflict with the Raiden Shogun showcases how her idea and pursuit of ‘Eternity’ has cast Inazuma into a dangerous state. Inazuma’s books in particular seem to voice out the concerns of the region’s mortals, with flavor text narrated as them, “we mortals”:

Transience is the dream of the nation of thunder.

Fleeting glories are the highest expression of mortal beauty, for are we mortals not like the flashing lightning itself? Like a lovely dream or blossoming spark, we shall leave a gorgeous mark on the eternal night sky.

One could say that these books reflect the ideals of the original Seven, but I’d wager that these are malleable, more likely penned by man to be reflective of present-day (such that the Inazuma books directly discuss Baal’s dream of ‘Eternity’: “The ruler who claims to have perceived all forever aims to hoard celestial glory…”).

While each Archon imposes their own systems of belief as embodiments of their ideal, human purpose is higher. Mortal ambition far more diverse, rarely contained regardless of how realized they may become.

Talent books reflect this mortal perspective on what flourishes, in forms that can contrast with what their god imposes.

Mondstadt’s storyline directly deals with the conflict between Freedom, and in a higher level, what happens when an Archon’s ideals are imposed:

EN: What does freedom really mean, when demanded of you by a god?

CN:被「自由」之神命令的自由,还能称之为自由吗?

A freedom dictated by the God of Freedom, can it really be named freedom?

Going back to the concept of ‘moral cultivation’, it appears as if Mondstadt will never actualize this with the presence of divinity. (This can depend on your personal interpretation on how ‘free’ Mondstadt is, and if freedom can truly be achieved under the current laws of Teyvat and system of the Seven.) What is freedom after all, when demanded by a god? Self-cultivation out of one’s efforts requires a more deliberate process, as if the provision of Visions directly counteracts this objective. Divine tools that attempt to induct ideals only go so far.

And Liyue’s, a “contract to end all contracts”, presumably Zhongli reneging on his initial contract with Celestia:

EN: In the end, he will sign the contract to end all contracts.

CN: 在最后的时刻,他将签订终结一切契约的契约

At the last moment, he signs the contract that shall end all contracts.

This doesn’t mean that Venti or Zhongli don’t believe in their ideal at all; freedom still paves the lives of many Mondstadians (“Me not wanting you to listen to the Abyss Order doesn’t mean that you have to listen to me”), and Liyue’s own people forge their own contracts and agreements that have led them to prosper.

Letting go of the rigidity of these ideals under divine rule, however, seems to be a common theme. In turn, people forge their own beliefs. These own ambitions and values may contradict that of their Archons. Like with their talent books, Inazuma’s Travails questions Baal’s pursuit of Eternity:

EN: “But what do mortals see of the eternity chased after by their god?”

CN: 追求「永恒」之神,在世人眼中见到了怎样的永恒?

“What kind of eternity will the God pursuing Eternity see through the eyes of mortals?”

(However, something interesting to note is that Venti and Zhongli hold English ___ Dei Constellations (Divine Stone/Divine Song) while Baal is instead Imperatix Umbrosa (similar to Shadowy Empress/Empress of the Shadows). In CN, Baal’s constellation is 天下人座 “The One Who Will Unite and Rule the World” that originates from Oda Nobunaga. Translated directly, 天下人 is meant to be a title for a human, not a deity…)

We also know of Khaenri’ah who flourished as the “pride of humanity” without any god at all. The immanent Archons manifest their ideals in new forms. The heavenly principles that appear to hold the world together fading. Are divine ideals necessary for mankind to prosper?

…

(Don’t make assignments! If it wasn’t clear enough. It’s important to remember that like Vision elements, these assignments are also not really based on any definitive identity. You can easily make a case for a character to fall under any of their nation’s books––or most other nation’s, for that matter. For gameplay reasons, people are spread out evenly amongst their region’s three books. With exceptions like Kazuha introduced pre-Inazuma and Tartaglia with Mondstadt books––things get a bit funky.)

5. Ideals can overlap, and they should

Given that humans seem to be driven by desire that can be anything from fleeting to ruthlessly pursued, and that humans have the inherent ability to just––believe in many things as they’re not the personification of any one trait… they cannot be contained. Our cast is rich and complex.

At the time of writing, we’re far away from completing many characters’ Story Quest series, and have people who have yet to be seen. We receive bits of characterization in everything from furniture lore to birthday tweets.

Seven ever-changing classifications will always be broad

There’s direct conflict between the embodiment of one ‘ideal’ and human complexity/purpose.

After all, before the time of the Seven and in regions beyond Teyvat, people flourished without being clumped into seven ideals. Human ambition and desire, even unguided by divinity, is insatiable. Perhaps even arrogant at times. Could this be related to the mortal arrogation that the Sustainer of Heavenly Principles fears? And what in truth, does gnosis mean?

I can imagine the Archons at war with the right moment to grant a character of a specific Vision. If we had a more binary classification system, things would be a little easier; but like the ‘seven deadly sins’ and how you & I could likely tick off more than a few and perhaps one stronger depending on time of day, our guesses can only go as far as the information we’re given with characters who actually have Vision stories. Trying to play with anything else is just like writing fanfiction.

A case could be made for a character and most elements, really

We do still have a mysterious ‘criteria’ and unknown motives for the provision of Visions themselves. So valid discourse might be like: “X and Y shares this trait that seems to fall under this Archon’s ideal”, but something less productive would be “What about Z? They could also have that trait, so X and Y exhibiting that would be meaningless”––since it’s totally possible. A non-Anemo person exhibiting Anemo similarities won’t erase the connection. There’s naturally going to be overlap and conflict when dealing with assignments for seven ideals and a cast of dozens of complex characters.

TL;DR

- Vision discourse is founded on the wrong things: tracing people to abstract divine ideals that are themselves questioned and flawed, and operate on different principles than the ambitions/desires that mortals concern themselves with

- Visions recognize mortal desire or ambition, of which one can have many, that are often far less realized than a god’s ideals.

- Language associates mortals = desire/ambition, gods = ideals

- Desire/ambition are regarded as lesser ideals.

- The past (Archon War) and present (God of Contracts signing the ‘contract to end all contracts’, Baal) display the irony of the gods’ own pursued ideals.

- Recognition comes at specific moments, which we have no information at all on for some characters. (The decision might even be pretty arbitrary, such as for gameplay, what sells $$$,)

- Under Confucian belief, welfare is related to moral cultivation from a nation’s leadership; hence the Seven are entrusted with the “burden of guiding humanity” under a divine ideal

- The Archons themselves are contradicting their own rigid beliefs, the Sustainer is dying.

- Mortal desire is more varied than heavenly desire; an order of heavenly principles > ideal > mortal ambition/desire

After all, is it wise to allow a moment’s ambition to dominate one’s entire life?

Notes, Addenda, Comments

- Fun fact: The Nine Pillars of Peace mentions “nine mortal desires” (though they’re pretty badly translated in English; vision here more closely means something like ‘focus’ 凝视)

- “Greed, nostalgia, vision, jealousy, anger, lust, self-aggrandizement, competition, turmoil… “These nine mortal desires may heal the world, or do it great hurt. Their fire will never diminish, and it will never fade… Thus, we lay down nine pillars to bring peace to end here the conflicts that plague this world.”

- If you’ve read any xianxia novel, you’re able to understand the analogy between cultivation and vision-bearing. Cultivation is a Taoist concept where basically, one hones their spiritual powers to let humans become immortal and be granted supernatural powers. Sounds familiar, right? One example is Vennessa who never really died but ascended to Celestia. Here’s what the wiki says about the webtoon: “She was told that great heroes would be chosen by the gods to dwell with them in Celestia, becoming immortal and protecting the world with the gods.” Fits well, doesn’t it?

https://www.reddit.com/r/Genshin_Lore/comments/ot3sb3/pyro_is_not_passion_what_vision_discourse_gets/h6v2lrg/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

- Regards to Barbatos’ idea of freedom share one with the talent book, I think it also due to he learned freedom from Mondstadt people aka Nameless Bard. They mention that in Freedom-Sworn sword’s lore. https://genshin-impact.fandom.com/wiki/Freedom-Sworn

“They say that a region’s character follows that of its archon, and that this holds true both for the people and the land itself. But was it the unfettered archon who bestowed a love of freedom and wine upon the land and people amidst conflict? Or was it the people who nurtured the Anemo Archon’s love of freedom as they pined for it amid the howling wind and frost? This is a question that can no longer be answered.”

https://www.reddit.com/r/Genshin_Lore/comments/ot3sb3/pyro_is_not_passion_what_vision_discourse_gets/h6uw21t/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

- Ambition was an interesting word to use in english but the direct translation used from chinese is 愿望 which might fall closer to “wish” or desire. Ambition might imply the individual has more control/drive than we think during their moment of being granted a vision and wish makes a bit more sense in context for cases such as Qiqi, where rather than an ambition of life it was her final wish to live during a moment of complete powerless that resulted in a cryo vision.

- Another interesting thing to add would be the case of Diluc and JiangXue now that we have Inazuma NPC’s to compare to. This may back up your point about visions representing a “momentary” instant of ambition, the Inazuman’s who lived lives closely related to the goal that originated their visions are the ones who suffered the most losing their visions. Comparatively, Jiangxue appears not to be suffering any memory loss and is still in tune with his powers while giving up his vision, his life goals might be assumed not to be consistent with the same goal that granted his vision initially. Similarly Diluc was able to leave behind his vision without side effects after his father’s death because his vision was previously associated to his ideals during childhood but those ideals have drastically shifted after he ages and learns more of the knights. After his return with a new ambition in mind he is still able to pick up his vision again for regular use.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Genshin_Impact/comments/ot3oyl/pyro_is_not_passion_what_vision_discourse_gets/h6unsau/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3