This essay was initially commissioned & published for Carrie Hott’s Our Shiver, a solar-powered server at the Lab, San Francisco. This version exists as a mirror on my blog in addition to this HTML one.

From the pisonet, the aircon, the data center, to the POGO

In the archipelago, technology swells at every extreme.

All matters are now in service of machines: land, sea, body, mind.

The Filipino is a weather machine.

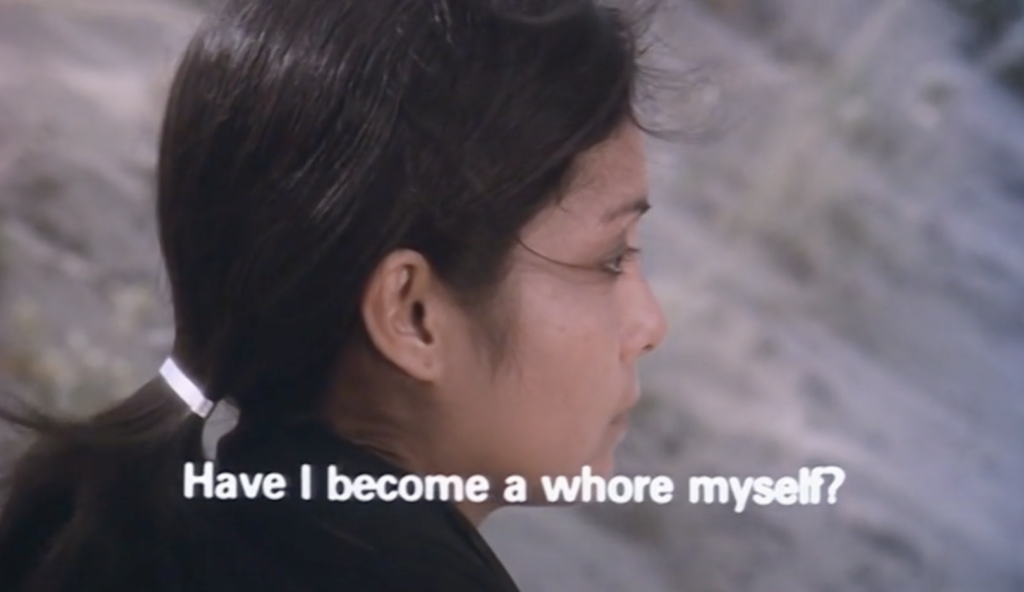

There’s a video of a computer shop in Cainta, Philippines where the floodwaters go up to the thighs. The boys have their headphones on, their polyester shorts hiked up, still playing Crossfire. Empty chairs and wrappers float up, and power cables run from the top of the room (precautions from previous storms). We know all the storms by name. We play with our lives. This is the image of the tropical technologist.

If technology is largely characterized by human manipulation of the environment to its ends, then the archipelago’s struggle with technology is one of constant weathering. Air conditioners relentlessly whirr in attempts to regulate heat, winds signal us to shelter, and satellites patternize all beyond our control. At times, nature attempts to reclaim itself, standing against all we’ve done to contain it. We respond in turn: more wires, infrastructural messes, generators, messes our bodies together. Much of nature’s wrath is just natural consequence. Rapid industrialization and urbanization irreversibly alter climate, unruly disaster predictions understate chaos, it rains inside data centers. Environmental inputs don’t just provide suggestions for sustainability, but become the mediators of their possibility. Our command of technologies is inseparable from the climates that it emerges from and is used within: so much that the elemental embodies the technological, and the technological constructs the elemental.

Third world technologies present alternative imaginaries for environmental computing that reject utopian visions of control. A tropical technologist embraces intermittency, seasonality, and scale, acting as a steward of land and machine. Living between extremes of dry and wet, blackouts and fragmentation shutter our attempts to control the weather—we merely adapt, memorize, survive. Ecologies are read as cybernetic systems; all environmental instability merely responds to human attempts to reign over it. “The earth is a machine of variation,” describes new media theorist Jussi Parikka. To borrow from the land of excess and leftovers, we’ll look over studies of technologies at different scales—examining how the tropical technologist might navigate, establish, defy, reinvent, and be imprisoned by the ever-blurring lines of atmosphere and machine in the age of the anthropocene.

THE PISONET

For people in the peripheries, life is lived in bundles of small plastic packets. Shampoo, coffee, seasoning, and toothpaste hang across the beams of neighborhood stores, often purchased by the many who do not have disposable income to buy more than sample-size goods. We drink small pours of soda in plastic bags, wash the bags clean and store it in a plastic bag of plastic bags. These same sundries sell prepaid load cards for mobile data for as low as US$2, connectivity in fragments. Tiny mountains of the rubbish of our lives pile up in street corners, shining in every color.

The third world sachet economy extends to the technologies we use, perhaps best exemplified by the pisonet machines that arose in the late 2000s. Pisonets (piso internet) are coin operated computers encased in wooden arcade machines, vending minutes of internet use for as little as PHP1 (US$0.020). They function as an even more restrictive & incremental alternative to computer shops (which also offer timed access), set up by local entrepreneurs in provincial and slum areas where many lack their own machines or where cellular connectivity is too poor. (In the Asia-Pacific, Filipinos have the highest time spent on the internet, some of the more expensive rates, and the slowest internet connection speeds.) Other alternatives have emerged: there is also the more miniature piso wifi, another connectivity vendo that provides internet access (no machine), in case you have your own phone.

While the western world enjoys ubiquity and speed, the tropical technologist faces exorbitant costs and connectivity issues, assuming they are able to be welcomed into the network at all. Because of this infrastructural poor, we find inventive yet capital-driven solutions to connect to the rest of the world with internet offered in sachets. Across the archipelago, the pisonet attests to the fragmentation of access itself.

Recent years of record heat have caused unprecedented power calamities. El Niño’s1 heatwaves stress Manila’s centralized power grids as fans and air conditioners blast and hydroelectric supplies damper. In May 2024, at least 23 power plants across Luzon went out. Governments begged for the public to minimize use as the heat index soared to up to 46°C.

Pisonet owners begin to find inventive solutions: after all, the machine itself contests the fragmentation of our archipelago. Low-cost solar setups arose as popular add-ons, plopped on top of corroding aluminum roofing, helping offset exorbitant electrical costs while guarding against power outages. We make our own distributed grids, find localized ways of living amidst crises. Boys continue to play through the storms.

Reductionist views of the tropics might associate it with dysfunction, (urban) jungles—a backwards world. We are a proper poor, where lights flicker and we boil water in kettles for hot baths. An island atop of fault lines always on the verge of an end. While the other side of the globe might enjoy increasing efficiency that in turn, leads to continued extraction—simply hungering for more and more. Compute is the new oil, after all. But there is something beautiful about the necessary roughness of scarcity: we reject ubiquity and everywhere-ness, we use only what is needed (because that is all we have), the slowness of our infrastructure actually present the truest mode of sustainability beyond the harnessing of the sun: simply needing less.

But in the tropics, bodies and time are slow. We watch over each other’s shoulders, heckling one another in cramped spaces and alleyways. Access is precious—so we inherently adopt a kind of intentionality with technology that times itself with natural resources. Bandwidth limitations further aid this sometimes unintentional sustainability: we load low-resolution images from off-market phones (if they load at all), stream in 240P, live with throttled download speeds, and sometimes can’t access more than a handful of sites at all.2 The computer is only ‘on’ when the sun is, not by choice but by circumstance. We are intermittent, islanded, and deeply intimate with the limitations of the land, as fluid as water.

THE AIR CONDITIONER

Where the pisonet suggests we might embrace intermittency and move towards slowness, the air conditioner presents a climate paradox. What if the technologies we’ve relied on to survive are the very cause of our suffocation?

The modern air conditioner was invented in Buffalo, New York in 1902 to help regulate humidity in a publishing house. It spread to flour mills and Gillette factories, devised for industrial productivity & quality, with the tolerable temperatures for laborers being a mere side effect. It was re-explored for comfort reasons a few years later 1906: theaters often shut down in the summer due to the heat, but the air conditioner could change this. So led to the rise of the summer blockbuster and the shopping mall.

Later, on the other side of the world, the Crystal Arcade of Escolta, Manila opens in 1932—the Philippines’ first air-conditioned shopping mall. It is destroyed in World War II.

Under brutal temperatures, Filipinos flock to malls for their conditioned atmospheres. Within, everything is controlled, it’s not just the weather: every service imaginable at every price range advertised, where a nation’s urban sprawl has delegated it as the public space, a proxy for parks, the beacon of modernity—clean and cold, the opposite of the city. Metro Manila has 317 hectares of urban parks and 368 hectares of retail space occupied by the top ten major shopping centers alone. The mall is the city itself. Public transportation routes go through Mall A to Mall B. I went to church inside a shopping mall.

It is no surprise that the American mall is at its deathbed while the Philippine supermall thrives. Here is the tropical climate crisis, there is no pisoweather and only the big players can talk. Microcontrol of the weather at the expense of the macroclimate, where Western stores and mass profiteers control the flow of our bodies in exchange for our purchasing and servicing. In the summers, malls experiment with cutting wifi and AC to avoid immense crowds. Malls and air conditioners become extensions of colonial control.

How much of this is to blame from centuries of western shaping? Malls, capital, waste, and excess. Stores are lined with western brands, we follow western trends, speak in English and make our voices sound neat. Upper class Filipino culture is mocked for their reliance on air conditioning: from their air conditioned homes they step into air conditioned vans and then get dropped off right in front of air conditioned malls — sun-kissed skin and sweat are symbols for poor, for lack. We once roamed the seas.

The Philippines is no stranger to colonial technologies: karaoke from the Japanese provides moments of solace, bahay na bato (stone houses) from the Spanish style most ancestral houses, and jeepneys from refurbished American military vehicles have become a reclaimed national symbol. Today, the American air conditioner is a new colonialism: our reckless attempts to control the weather driven from capital, and the long-term climate collapse that comes after. Cooling, an invented privilege, becomes an inescapable cage of our masking, dotting skylines with wires and mess.

There are limitations to blaming the individual consumer, even if it’s a favorite option. All these issues stem from systems and scales larger than what we can comprehend. We feed from plastic because we have no choice; the sachet economy is a result of corporate greed. How are we to blame the vulnerable and elderly for a reliance on cooling when the heat kills? First world countries import their waste to the third world, with the United States exported 276,200 shipping containers worth of waste to developing nations in 2017. In the gated suburbs, there is one air conditioner turned on in the whole house, and a family of four all sleeping together in the same bed. The subtle drone in the air is the ambience of upper middle-class Manila. There is a network that is always on elsewhere, drawing computational power from the many hungry.

THE DATA CENTER

If the urban tropic is characterized by its entanglement with the colonial project of malls and the consequences of air conditioning, the rural tropic faces its industrial equivalent with the data center. As digital infrastructure demands physical space, we continue to create artificial environments. Still, we face a real reality: our lands are turning into clouds.

50 MW capacity VITRO Sta Rosa opened its doors in July 2024, boasted as “the nation’s first true hyperscale data center.” Data centers offer centralized solutions to computational power, storage, hosting, backups, and other technical needs at continental scales. VITRO aims to attract foreign investments, servicing tech megacorporations and other Asia-Pacific players, even amidst infrastructural challenges in an already resource-stressed archipelago. The same month, Typhoon Carina batters the country. Floods lead to surging power demands, the island’s power grid goes on yellow alert, with 300,000+ homes losing power.

Telecommunications giant (and monopolist) PLDT has been in the data center game since 2000, but in recent years, demand has soared. The company’s data center capacity was at about 146.2 MW in August 2024, but PLDT is already eyeing its next and 12th one, dreaming of twice the capacity. New facilities seeking to cater to AI’s needs, which have even higher energy demands. Each year, capacity is now expected to double or even triple. To meet these capacities, these centers will need renewable energy solutions (to hold off storms) and liquid cooling systems (to withstand the heat).

Department Circular No. 2017 prescribes the Philippine Government’s Cloud First Policy, dictating that government departments and agencies accelerate towards cloud computing adoption. Plagued by bureaucracy and legacy systems, the circular continues to describe cloud services as ‘robust’, ‘up-to-date’ and ‘state-of-the-art’, comparing Singapore, Saudi Arabia, and the United States as successful peer adopters. Data sovereignty is also invoked: “no such data shall be subject to foreign laws, or be accessible to other countries”—the cloud must only rain above our territories. Bidding for the Subic Data Center, the key to the National Government Data Center project, began in 2023. As of 2025, the center has yet to stand, in part due to budget constraints.

Other corporations aren’t ready to bite. The SM Group, the largest national conglomerate (who own 89 shopping malls in the country, all prefixed with SM) cite expensive power costs and calamities as risk factors. Interruption is disaster. These machines do not fail gracefully, they fail all at once—any downtime is an immense loss. With SM in the business of malls (masters of profit) and PLDT in monopoly with weak telecommunications (with little incentive to improve services for the general public, especially due to no competition in the current duolopy) probably stand at opposite ends of the spectrum for a reason.

Individual attempts at decentralization are still throttled by the giants of the network. Last year, it was estimated that 60,000 telecom towers were needed to meet the demand of the archipelago—while only 12,000 independent common towers existed. If we’ve been throttled for decades on cellular investments, this attraction to the ‘hyperscale’ data center makes priorities clear. (The same conglomerate owns both PLDT and Meralco, the energy giant that covers 55% of the country’s electricity output, including Sta. Rosa.) The populace still suffers from an increasing digital divide. If we consider cooling, take the blame on the individual and multiply it ten thousand fold, and you’ll have a rough picture of the needs of an average data center. Machines in farmlands carry the weight of nations beyond us, while we can barely sustain ourselves. Digital land has become more precious than physical land.

Once, we listened to creation mythologies that described the beginner as all sea and sky. We move towards a world of cloud: all our resources are slowly being reclaimed to host a digital ephemeral. Land, water, and energy all face insecurity, yet we are more invested in controlling the climate for computers rather than ourselves. In my childhood home, the fans point not to us, but to the computers so it is possible to work.

As these battles broil, I can’t help but think of the adjacent battle farmers face. Under incessant heat, timing their workshifts to end before the heat causes it to become physically impossible to work. But the sun is no issue when there is no more land to sow. Land grabbing illegally seizes the livelihood and homes of peasant workers, handing over hectares to subdivisions and complexes. At the border of Sta. Rosa, Calamba, and Cabuyao sits the 7,100 hectare Hacienda Yulo, where farmers have been violently losing their land since 1911 due to contest from real estate companies. Those who enrich the land are the poorest, and those who build for the cloud profit.

…they returned and set on fire Mangubat’s house even while his wife Dottie was inside.

THE POGO

In June 2024, Filipino authorities rescued 207 human trafficking victims from Lucky South 99, a 10-hectare gambling conglomerate in Porac, Pampanga. Porac is a developing industrial hub with agricultural roots with hectares of farmland are for sale on Facebook Marketplace. Think of what Menlo Park is to Meta, except to an illegal business nestled between fields and a golf course. (Lucky South 99 was mounted on 10 of 46 hectares of land that were illegally seized from farmers.) At least 40 other facilities in the province were raided.

Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators (POGOs) are umbrella terms for predatory online services like electronic casinos, sports betting, scam hubs, clickfarms, and cryptocurrency schemes. POGOs largely service clients from other Asian nations, mainly China (which has banned casinos operating in the mainland), and multiplied during the 2016 presidency of Rodrigo Duterte. Smaller operations take over apartments and condominiums, gentrifying cities—but POGO hubs rise to meet multi-billion peso demand, forming industrial parks with company shuttles, dormitories, grocery stores, karaoke rooms, training rooms, Olympic-size swimming pools, and torture rooms. Inside, distressed workers with no choice. POGOs promise economic growth and job stability, but the scale of these illicit operations make way for abuse, human trafficking, and murders. Love scams (also known as pig butchering), crypto fraud, and gambling sites run with the quiet support of politicians and real estate giants, invested in money no matter how it is made.

The issue is beyond the Filipino. Lucky South 99 rescued 158 foreign nationals, many women were sexually trafficked and men were tortured. Most workers are swept away from their home countries with the promise of lucrative, digital jobs—and are suddenly stripped of their passports, goods, and eventually their identities, stuck in these compounds in a foreign country. Female victims awaiting deportation back to their home countries are sometimes pregnant, with what is now termed as ‘Pogo babies’. If you’ve ever stopped to question who are the people behind scams, did you ever guess that it would be modern day slaves? A whole economy has risen from preyed people preying on people.

It is not just POGOs that are in the business of exploitation. Many rebrand to call centers and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) hubs, industries which contribute 7–8% to the nation’s GDP. Globally, companies from tech, education, travel, to finance outsource customer care, IT, data labeling, and other menial service work to the Philippines. While BPOs are also a big sphere of operations, they are not without their abuses, built upon a distancing between the exploiter and the exploited. ‘Innovation’ happens on the other end; the dirty work is left here.

Tropical bodies serve as technological infrastructure. It’s not only our land and resources that are extracted, but our bodies too. Humans label, screen, tag, and order data needed by AI, sometimes even performing the work themselves under the guise of AI. Content moderators clean social media feeds of extremism and gore in dehumanizing conditions. Virtual assistants become the backbone of digital businesses where labor is cheap. Semiconductor factories pay substandard wages and union bust as profits rise (electronics account for about 60% of national exports). The tropical technologist has been perfectly engineered for this role: valued for their proximity to whiteness, cleanliness of voice, and their lack of choice. All these make ease of our erasure, where progress seems to involve removing, or more precisely, obfuscating the humans from the equation. The tropical technologist is continuously undermined as slow, inefficient, cheap, and backwards—even when our actions are the very determinants of ‘progress’ for much of the world. Not only do they want our bodies, but they want our very identities.

We might be the most resilient machines: operating despite our land, mind, weather, and bodies ripped from us, slowed down by systems beyond us, servicing without question. We are cyborgs as Donna Haraway might place it, the results of both a social reality and the many fictions that have been ascribed to us, struggling with the new modernity. We might be the beginning of the world’s end and the country of the new technology.

THE TECHNOLOGIST

As an archipelagic people, we know the soil, semiconductors, and seas. We weather all that come with it, live in accordance to the storms, face the realities of all conditions once hidden, and respond to ecologies beyond our control. The tropical technologist has given their land, mind, and body to the machine. The tropical technologist has become machine. For all divides of low and high technology, we are its backbone at every order. Technology has reformed all nature, and this is truest in its reformation of the tropical human into an exploited, but well-oiled machine.

The pisonet models the fragmentation of the tropical technologist and their resilience; the air conditioner points to the entrapment of our people to capital and colonialism; the data center speaks to industrial priorities and amidst a national crisis with ongoing disregard to the land, food, and energy crises that the populace needs; and the POGO reveals the explicit degradation, violation, and undermining of our identity, with our bodies as infrastructure.

As the human that has become machine, our tropical bodies present alternative ways of being. Just as we once constructed machines to extend human capacity, we might reconsider the ways we decentralize, use, and live in this age: to embrace intermittency, adapt to the sun’s energy, prioritize localized infrastructures. But, where solar-powered servers and low technology are choices in the western world, the tropics remain plagued by larger infrastructural gaps. The least we can do is take action to prevent the continued deterioration of ourselves and machines. Our lands are razed by corporations, connectivity remains limited, the world’s systems are built off our exploitation, and face one disaster after another. We are not helpless, but we also are a cautionary tale: climate instability is only intensifying, and the third world will no longer be able to shoulder it alone. Let the tropical technologist be visible—look towards those who have stewarded both the material and technological worlds most closely.

Our relationship with the environment turned technology is one of becoming rather than dominion, a symbiosis that knows that technology reconstructs the human as much as human makes technology. Instead of supremacy, there is stewardship. In this archipelago, we’ve become both weathered and weather. Our bodies run off fire and water, we continue to play in floodwaters.

Technology was once a process to separate ourselves from nature, possessing it. Now, technology is our becoming-one-with-nature, a return—as the tropics have always felt it.

- El Niño is caused by warm surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean, leading to intense droughts and water scarcity. ↩︎

- Facebook’s Free Basics plan was once tested in the Philippines, providing free access to mobile data but only allowing access to a limited amount of websites. Most people just went on Facebook. ↩︎