( In the move to radically reinvent a ‘poetic’ web, I motion to look at the spaces that we have already cultivated. That digital intimacies are not just ‘built’ or ‘resolved’—that the act of cultivating this internet is beyond the hands of any technologist alone: it is in consciousness-raising, recognizing the dwellings and spaces people have already cultivated, and intentionality over what institutions & politics we are modeling this new web after.

We need to broaden the label of who is a technologist—recognizing the people actively dwelling amongst our technologies as those shaping it. Instead of searching for a supposed ‘essence’ or ‘purity’ to technology, we should name the way the most impacted are already dwelling in it—legitimizing how people are actively constructing this reality, guiding us for how we will construct the next. Softness cannot be optimized for or solved with software. Technologies are relations, not objects to be solved. )

( still a work in progress and being written in public… this can definitely be shorted and chunked down, but i wanted to just write and think. :b )

In this final, stultifying stage of capitalism, we are moving from poetic technologies to bureaucratic technologies. By poetic technologies I refer to the use of rational and technical means to bring wild fantasies to reality. Poetic technologies, so understood, are as old as civilization.

They could even be said to predate complex machinery. Lewis Mumford used to argue that the first complex machines were actually made of people.

A web as a social act and becoming of the century

Like with any worthwhile thing, we gathered. About a decade ago, ‘getting on the internet’ was the act of the century. If you were lucky enough, your household had the family computer room with a bulky Dell set-up, trackball mouse and all, next to mounds of file cabinets. An Rx Prescription Pad was our trackpad, aptly soggy from the Coke Zero condensation pooling onto it. I couldn’t take a 30 minute time limit per day on weekends, so the next viable option was to sneak out to computer cafes. My sister and I would sit down together, fingers pointing at the screen dictating each next move, making interactive stories on PowerPoint. When I was given my first hand-me-down laptop, my friends would come over for impromptu recording sessions with the built-in microphone to overdub YouTube rips of the Neopets PlayStation 2 game. Trips to the bookstore at the mall after school also included “needing to print something at the computer cafe” which meant how many League of Legends games could I play with decent ping, back when every guy & girl I had a crush on smelled like shit and played like shit in this space that swept up every bad signal—all I cared about was that we were here, doing something together, and we loved it.

Now, desktop & file system metaphors are disappearing and we use our own devices as our gatherings. After some decades of placemaking, corporations have become sordid answerers to the desire for connection. Centralized social networks become the primary spaces we congregate in, almost no different to the density of mall culture I experienced in urban Manila where privately-owned public spaces are the norm. It’s not the prettiest picture: the sense of community in an internet cafe with several signs up saying “NO MASTURBATING ALLOWED”, but we gathered around it, anyway. It was in this time that the internet felt closest to a medium for connection, rather than the sole place where connection was transacted in itself.

Yet, there remains significant political contention over whether internet access is even a right—despite it seemingly (and rightfully intuitively) being so embedded onto our social grains. Its social ubiquity might be our intuition, but the position of the internet has extended itself beyond how we merely feel about it and how we need it to live. We saw serious ramifications of this across COVID & healthcare and are at risk of losing recent human history with the deaths of these platforms, if you consider them alive at all amidst the ideological shift. The ridiculous question of whether it should be a public utility or not will continue to be toyed with by massive service providers and political pawns wondering about the expensive of innovation and questions of hyperlocal governance if we ourselves don’t recognize all its simultaneities: that it is a place where we can fall in love and be loved already, that it is a place where movements are born and where individuals have been killed, that is a place that is terrible and wonderful, that it is a place that can be participatory and alienating, that like the real-world will begin with mirroring broken structures. That it is just like the real world.

So I won’t tell you that the internet should only be filled with highways or gardens. It is an entire world unto itself, one with complex interoperable systems that require for it to function, many with evolutions that we are only beginning to dissect in its short history. With the internet’s infrastructure, our placemaking might begin with analogies to ideals of libraries & fields, but should continue with using this technology’s unique affordances & nascency to reimagine how these physical references might be made even better, and should continue even further with the constructing and naming of places that only exist on the internet. As the file metaphor dies just like the Garden of Eden, I wonder what imaginaries and subsequently constructions will become part of the internet’s own mythology. So I won’t answer whether our thinking of the internet, especially from this heavily technological perspective, should draw from architecture or whether questions of governance & politics should guide it more—the answer is everything. This is why we begin with and always return to physical associations, and why more technologists must embed history and the humanities into their practice—for technology itself is a human practice and construct. When we talk about building rooms on the internet, we also talk about the entire world the internet is positioned in and all of these ecologies. We need to also talk about flow of labor in the construction of these rooms: ending at the website hosted on a corporation’s server with a quirky Top-Level Domain managed by an operator you are unaware of only invokes the handmade , but to what extent? Is it mostly for the aesthetic sense? There are very real physical pieces behind our fantasies for a softer web, one that most of us are incredibly detached from.

Softness is a valuable strategy to undermine the web today. I believe this love is central, in fact, which is why we must recognize the love that is present. It is why I myself move towards a poetics of the web, have written about tiny internets for years, and have retreated to the internet to invent these worlds for as long as I can remember. I am interested in gathering all the people I love in one place and genuinely believe the internet could be this place. I taught my friends to write HTML with glitter pens in middle school and made it the activity, starting a ‘Webmasters Club’, and then struggled for years after to teach hundreds of Filipinos how to code and think in the realm of computing—a struggle I still work on, with both tech-savvy technologists in our scene at a time of a bubble’s bursting and a more tangible destabilization from political disinformation campaigns within an industry that largely undervalues and obscures the work of the mass Filipino tech worker. So I will ask you about participation and who is shaping the web in your imaginary: if your parents are a part of it, who you are looking to be intimate with, what languages you imagine this web to speak or birth, if you know who is already shaping the internet you operate in, and how you have intersected the internet with the world you live in. I’m conscious: is our reimagining and reclamation a collective act? Who is building it, and who is it built for? Is it a respite from something? Are we already aware of the current world it exists in? Who is holding the tools that shape this world? What structures and political dynamics are you reinforcing in your internet? Does this tenderness only serve you?

Sometimes I fear that my fascination on the web’s malleability and my belief that it can be reshaped will lead me to succumb to the same mistakes. I cannot reduce the internet, as we all could reach for pen & paper and still seem to have little to write. The seemingly overwhelming toxicity of one streamlined, constantly pushing feed was all-encompassing, cosmic, nearly god-like in its promise for agency for you to rewire it: with the lines of code to do so. It is in this reduction and this belief of reshaping that agency might again be merely illusory. There is concrete, verifiable need to carve more caring spaces and the same need to question that place of care—especially when this call is forwarded by technologists (in this meaning well-educated or independent software engineers, designers, etc. who seem to be at the forefront of net art and the handmade web movement) for the supposed sake of all.

The internet doesn’t have to be like the real world. The internet is the real world. There are no dualities, there are only the deepest, oldest, and forever unanswerable questions of social theory that must permeate our thinking. There is my simple human question of the way we frame this technology in relation to its place in society that I want to better interrogate: what we consider as technologies, who forms it, its form, how it’s felt—before I can continue my unending pursuit of bettering its future.

I want to tell you that there’s an internet that’s mine and that you could live in there with me. I want to know what internet you’re imagining. This begins with a recognition of lived experience and all the experiences concealed to us; my life on post-colonial property and the truth I’ve found on the internet. I think, the beautiful thing about this technology and the position we’re holding in shaping it is that it is indeed malleable and growing and learnable—that it is built upon technologies and the life work of thousands, that it is actively served upon technologies I’m still learning to even see and name. And that we can open up this question for the entire history of technology is in relation to how we’ve gathered and interfaced with the material world. I argue that more than a question of tools, the question of technology is one of changing minds. Instead of a technosolutionist perspective of resolving the internet or an ideal of it being something that is just ‘built’, we must question how we live in it, who participates in these structures and its sociopolitical implications, and the nature of participation & exchange we expect.

A web as sanctuary and the meaning we make of it

I’m constantly skittish about the likening of the web to the physical world not only because wading through file cabinets for signature slips was a painful task. It’s because the internet, growing up (and until today), was a sanctuary against the real world. My life was waking up at 4AM to commute to school, oftentimes only getting home at 8 or 9PM or so; we would never go out if not to the church, mall, or the province hours away to see grandparents where there was definitely no internet. Life was incredibly solitary; my parents were constantly working, the television was boring if not broken, and my Catholic school offered machinic routine, historical revisionism, and religious fearmongering in their stringent task of putting these middle-upper class kids into four potential universities and fates. This flavor of repression is nothing new; not only because my closest friends on the internet share the same whether born a two-hour 15km drive away somewhere else in Metro Manila or an American stripmall town, but because any controlled society has dictated a certain brand of life. Even small, hyperlocal institutions often come with marginalizing, classist, and racist histories, if you live in a place where they are accessible at all. Sometimes these histories aren’t even swept under the rug. There are technologies older than the computer, programs just a recoupling of ritual routine, and a truth in the tool: people have been made to feel like machines for centuries.

When I didn’t then know that I wasn’t a girl and wanted to hold girls’ hands and didn’t know that my fate after earth was not only hellfire, the only inklings of this then-radical thought were planted from this device that opened this world that felt like magic. I learned that there was a name for the things I was feeling and they were real and did not have to be repressed (just concealed, for now), and they had answers to the ones religion didn’t give me. I fell in love online and it felt more real and constant than the broken images of love elsewhere. I spilled 2% milk on my keyboard and discovered porn too early. When I had my first kiss, I wondered why it didn’t feel as special as working your way through someone in Skype—knowing them slowly, piece-by-piece, knowing them wholly to whatever wholes we could give then. It was another social practice without meaning to me, unlike the meaning I projected onto the internet.

It feels weird traversing this ahistory with anyone else who grew up online. Together, we recall dead company names and the sound of slow broadband speeds, using the sound of clicks entwined with imagery of ourselves with our laptop on the kitchen counter, with jumbled representations that remind me of how the digital world can only ever be represented with the physical. I’m carrying a bulky laptop overheating itself with Warcraft 2 up the creaky stairs of my grandmother’s house, past all her statues of Jesus and Mary; I snuck in the computer to our annual school field trip. Sometimes I remember the digital more than the physical, other times the other way around, while each persistently reminds me of this world where it’s up to us to define and construct these boundaries.

The highway of the internet was congested and filled with dangers, but I could begin to express myself—a task which in the real-world, was often punished with physical, verbal, or financial abuse and harm. There was so much of myself that I could begin to name and so much of myself that I could then imagine becoming; an expanded lexicon and consciousness-raising of the terms of my living in the Philippines was only afforded by the internet. Today, I fear legislation and control that robbing marginalized & queer youth of these opportunities to discover themselves, and general regressive public sentiments that claim specific, often folk and queer-run internet spaces are brainwashing youth. Worse, ‘innovation’ that points towards access that rob people of agency and strip them of potential consciousness-raising; as in my often quoting of the Facebook Lite/Internet.org ramifications onto the global south.

I’m sorry that this story isn’t particularly beautiful or captivating. I had no magical mentor who gave me the opportunity of a lifetime, wise relative, or life-changing English teacher that saved me. It was the internet and the people in it that let me save myself. I taught myself what I needed technically and begged to work my first job, I can name you a dozen of this expanded family who have all fallen into this pyramid scheme with the most gracious thing they could give me is letting me run off on this old device, and our English teachers were explaining how adverbs worked in the 12th grade. The next year I went to Yale.

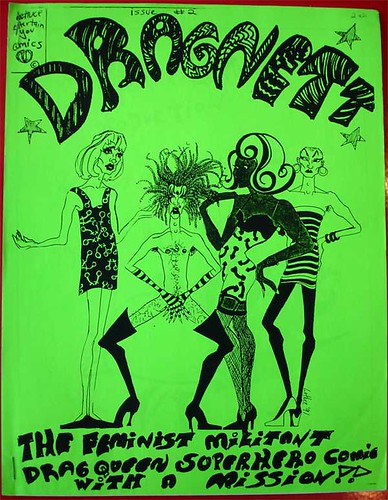

At my first semester at Yale, I touched my first ‘zine’ and didn’t get it. It was overtly loud and a bit too explicitly socialist with all the tellings of DSA-optimistic white feminism, punk when all my exposure to punk was through Hot Topic-commodified aesthetics, and delivered in a medium that would have found a more bitter end in my lived experience. I love my professor, in her mid-40s with such a voracious and wide-reaching heart for graphic design and by extension—projects such as putting feminist slogans on billboards (in a blue state) as “social practice”, but we once spent thirty minutes in class discussing indie publishing movements. I had never been to an independent or used bookstore before college; the closest one physically was three hours down in the province at a university I wasn’t sure I was allowed to step in by whatever club was organizing it and was sure as hell not allowed to go once my parents discovered that it was called a “zine orgy”. And this was already when I bought into it. I wanted to scream and become politically active and everyone asked me if I wanted to get myself killed. Entering any alternative space outside of a mall, if I could even find one, felt weirdly alienating: like I still was in Catholic school uniform and was deemed on visual & speaking basis, like I couldn’t participate in this struggle—a keeping that people often do rightfully.

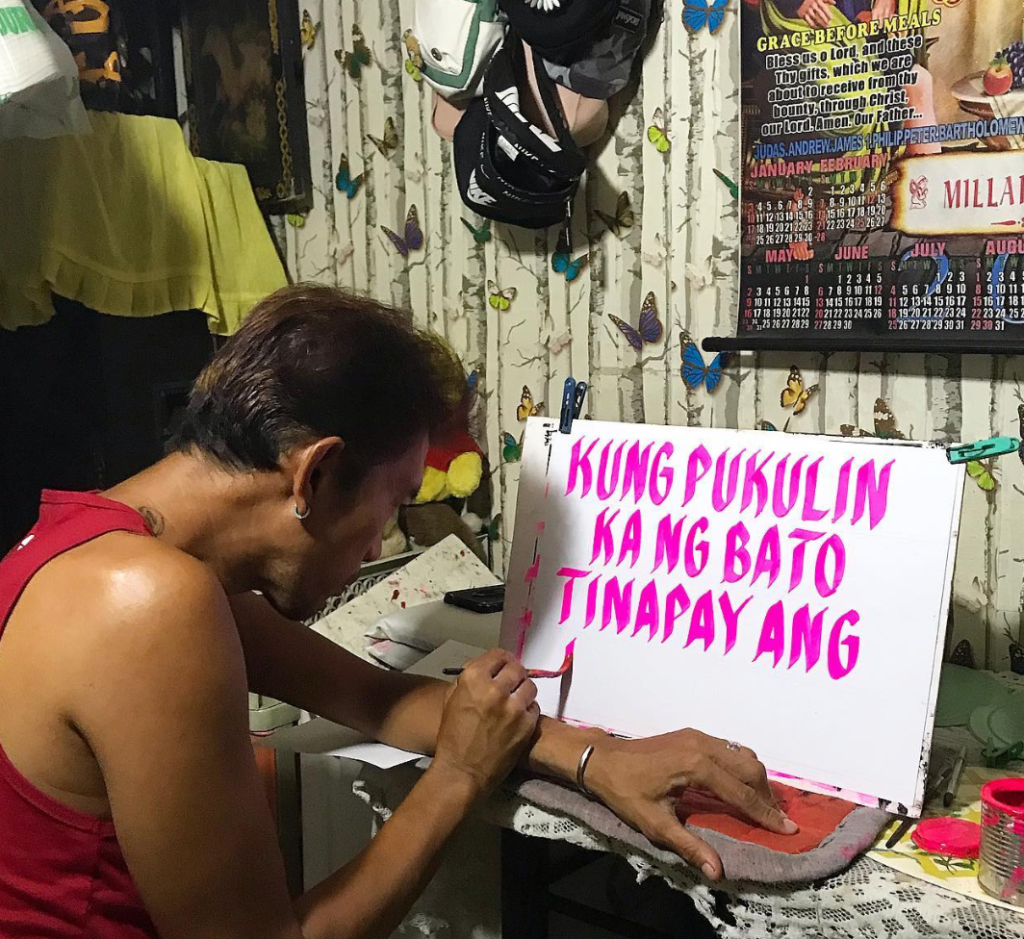

We talked then, about underground zine culture and its possible fetishization. The riot grrrl movement (one I have always struggled to identify with) and how zine culture in your school presumes that the school does not stringently inspect & confiscate documents for fear of blasphemy, or that there is some semblance of accessible punk or music movement that you can find at all, or that you can actually own non-empty notebooks and looseleafs without them being discarded, or that your school wasn’t already in some strict religious social hierarchy that scorned you for assembling clippings together, or that you could touch the newspaper filled with propaganda. The internet was still new and not understood and it wasn’t yet demonized by the priest in mass, safe from the destructive public world. We had our own equivalents, ones that took from these movements as they too must have trickled down from niche spaces to the suburbs. In a class I took with her again two years later, I took the prompt of ‘collecting’ to collect purely digital artifacts and captures. It was mostly out of convenience when I was locked up in COVID time in a house & neighborhood where I was afraid to really move around—feeling like the small person I was back in the Philippines finding relief only in the computer, which she didn’t take kindly. The other undergraduates collected junk mail and COVID signs, which were everywhere and equally thoughtless. If only I could articulate then what these acts of securing digital-native materials mean, that they are at larger risk of disappearance, that securing and treating them as precious as physical material (for they are all built on physical infrastructure) is a radical act in itself. This was before I had those intentions.

At the same time, I recognize that this faith in the internet is one my elders are distanced from — the social contexts which they might find on the web are completely different to mine. What values we have derived and what we have made of the web are different; the faith we put on these systems at a disconnect. Even amongst my peers, I reasoned that my own act of placemaking came born out of necessary roughness—as if there was nowhere else to go but the internet.

There were also a lot of bad parts to the internet, of course—particularly ones that I’d have trouble quoting to you with verifiable coverage. Partly because the internet used to be novel, and mostly because a lot of these ‘folk’, alternative spaces are now long gone. While the internet is infrastructure at its core, like any medium of human intervention it has become a complex ecology.

These bad parts, I learned to navigate with the resolve to the last paragraph—a plurality of selves that I could assume, a fragmentation and experimentation that could only occur as fluidly as it did in the digital realm. I made negotiations On the same website where I learned about alternative Philippine histories and what pronouns were, I was convincing people in their late 20s to not kill themselves. In this time of being young and naive, I hated the body I was in and tried to hate other things too. Sometimes it felt like I was a technical tutorial or 4chan thread (in that painful, brief period) away from being radicalized into something dangerous; a cautious overlooking I also do to my younger brother as he autoplays through different threads of thought, thinking that he is infinitely more brilliant than I am but also as susceptible to waves of extremism—especially as we both felt alone, against the world, brewing something in ourselves. No one outside could have seen this and woken me up from it. It is both a blessing and a curse that the internet could host secret worlds for myself.

A web’s rejection of the duality; technology is like a prayer

Perhaps I was like cyborg. One that Donna Haraway blurs between the physical and non-physical, denouncing the so-called polarity of public and private—all on the computer in a household form I would soon reject, in rejection of the Catholic organic family. “The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust.”

My cyborg self carried this notion of self that I could not express physically, but had learned to define in a million other spaces online. I carried myself in forums, in early iterations of Myspace and Friendster and hidden Facebook accounts, in the explicit worlds of online games and the implicit worlds of every other web, in chatrooms and the several blogs I would run. Where I would previously be erased and lost, I had the agency of customization and control (which was still illusory, but the CSS did apply and break my Myspace page)—I still look back to where I was on the internet in this past decade of estrangement, trauma, and restarting my life to mark where I was and who I had become. What artifacts I created as a child, what stories I was writing about myself or imagining and telling. Most of these selves were contextualized to the space, the same way even the most godliest of people assume a different self once they genuflect before the altar. It was like any technology: there was an act to invoke it in the making of a cross, and the clear technologies of prayer and scripture and bible and rosary—”just as the phone and science form moral sentiments.” Technology, when thought of as tools, are most interesting when we center on what they provoke and what imaginaries they expose us to. So both a prayer and a computer are rightfully technologies. They can both bring people to lie, to sin, to better the world, or to transcend.

When I looked at the world with these new eyes afforded by technology, I understood that all of vision and knowing was mostly man-made. Man-made does not have to mean manufactured. When the camera came and fell into the hands of the masses, we began so much debate in the ‘essence’ of image and the ways of seeing. In so much of theory about essence, I remember the seemingly illogical love for complexity and process in the hands of my relatives and loved ones who think no different the mall corner photoshoot booth for their Christmas portraits the casual iPhone shot on a trip, as what is held in image and the meaning made pays no respect to how commercial or blinding the set-up portrait shot was.

The computer and the internet are unlike many of our old technologies, but we can still use the same questions to guide our usage of them. Take the old technology of the fire, which ignites to signal gathering be it a grill, a cigarette, or a campfire: at its core, the nature of this media is to convert matter into other forms or make it vanish altogether. John Durham Peters says that the history of media is the history of the productive impossibility of capturing what exists. When we imagine a website as a room, imagine the caretaker and all that it is within—imagine the core of what it seeks to provide. A room, a vessel, a container, a space for rest, a space alone, a space that is intimate, a space we can customize, a space between spaces. We can continue to use these languages to open people to these gentle reimaginations of technology, and pay more conscious attention to whether it meets these qualities in the first place or if a more radical restructuring is necessary. The Metaverse is a joke not only because those extremely online know that VRChat furries have done it better, but because its replications of the conference room and office seem to just digitize all the things we hate about presence in real life.

Spatial software is a waste when we constrain ourselves to digital reconstructions of natural places, especially when we directly carry their qualities and forget that the beauty of a new technology is that it is always reinventing and building upon the old not just in form but in nature.

People believe there’s an essence to the computer, that there’s something true and real and a correct way to do things. But—there is no right way. We get to choose how to aim the technology we build. At least for now, because increasingly, technology feels like something that happens to you instead of something you use. We need to figure out how to stop that, for all of our sakes, before we’re locked in, on rails, and headed toward who knows what.

Frank Chimero, What Screens Want

One of the reasons that I’m so fascinated by screens is because their story is our story. First there was darkness, and then there was light. And then we figured out how to make that light dance. Both stories are about transformations, about change. Screens have flux, and so do we.

With the cyborg’s coming, there is no use to attempt to find one ‘truth’ in the internet beyond the historical truths of its use for exploitation and commodification with its privatization; we have been tracing for truth for ages. There is no ‘pure internet’.

There was the painting, which Andre Bazin declares was freed from the puerile obsession over realism with the introduction of the photograph, now satisfying a laborious eternalization of the unreal; then offset by the photograph in its ability to encounter not only a truthful realism but an entire new aesthetic world with autonomy, and “…the photograph allows us […] to admire in reproduction something that our eyes alone could not have taught us to love.” Then came the montage and moving image and thenceforth cinema. Then earlier too, was the newspaper with an impact that McLuhan describes of “immediacy and of super-realism”, yet with a metaphysicality that is existential—where the process of actualization is this impact. The newspaper parallels the endless digital scroll in our spectatorship, each one claiming itself as the story of our lives when all we do now is watch it tell it. I question too, what we can learn from other forms of media pushing intimacy and immediacy onto us, making us share in universal pain and joy and desensitizing us to all emotions—so much that feeling this intimacy could absolve us from acting, the same in recognition of a social ill sufficient when we continue to choose participating it. Digital media, the computer, our modern technologies, especially in their detachment in role of ‘tool’, as something that we use and moreso that happens to us, have complicated all these questions. Even this essay struggles with the multiplicities of its topic: everything is converging which had sought me to break free, and now I can barely unravel how all these forms have intersected.

A computer is not a city

This theory for unification isn’t guided by only a feeling, of course. Haraway also notes the need for unity of people “trying to resist worldwide intensification of domination that has never been more acute”, paralleling this resistance to the modern internet to any aggrieved social body. The issue now, is how to push and name this resistance when the ill exists with social, historical, local, and temporal simultaneities.

Fire is a chief metaphor for the Internet: it is metaorganic; it extends the range of (informational) food; it empowers people to explore new time zones (the night) and territories of knowledge; it increases some kinds of sociability, demands ongoing maintenance, and produces dangers and externalities that did not exist before. Fire was the first World Wide Web, a fragile system for contagious spreads. Young people now stay up late looking at flickering firelights—TV screens, computer monitors, smart phones—as they once tended the communal well of flames. (Television has always been compared to the family hearth.)

The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media

Chris Anderson, the chief curator of TED talks, in a short essay called “The Rediscovery of Fire,” extols Internet videos for restoring the power of the embodied voice speaking around the campfire. We “burn” discs on our computers. Memes and themes tear through the Internet like prairie fires, or are retarded by censorship “firewalls” such as those of the Chinese government. The server farms that are key to the material infrastructure of the Internet generate vast amounts of heat, requiring air conditioning in addition to the electricity their processing takes up. (Data centers are often built in cold climates to save on cooling costs.) Touchscreen technologies fulfill a certain fantasy of touching flame. As Paul Frosh notes, “Television and computer screens (including iPads etc.) have some of the qualities of fire, especially self-illumination; unlike cinema and print, they are lit from within.” Information is irreducibly connected with heat and burning.

We could pray for technology, but there are no definite roots to return to—historical or physical. The goal of the internet was always privatization, the infrastructures holding it up now reliant on underpaid and exploited labor in the global south, and It is only in the reclamation of the internet’s spaces post-ubiquity that we have begun carving these spaces for genuine expression and respite. For whatever we choose to carry in the new web, we should look to the human history and ingenuity in creating places for ourselves against oppressive structures both online & offline. Flowery metaphors and poetics are critical for extending our imaginary and beginning to suppose these new futures, but we must be aware of the implications of the languages we employ. A city is not a computer and a computer is not a city. Arboreal language helps explain the root to the tree and branches; it is no surprise that the University is technology for this reason, and that we are just in a playground resolving Git conflicts disembodied from the biological complexity within and around us.

As in Buckminster Fuller’s belief, we must find some way to live synergistically with the system of nature, learning from the principles that make the world around us, as we took the hexagon from the bee to come into motion and fly. However, its application has not always been generative in this ideal of synergetics. The cloud metaphor has concealed the vast amounts of labor and human infrastructure on the internet; the theft of artistry for ‘innovation’ and the grunt work used for AI data set categorization; urban & machine intelligences promise us smart cities with the thinking left to the machines and have many times nullified the humanity & history present in our own human intelligences.

At the same time, I can understand that with sachet culture and the (often intentional) inaccessibility of more eco-friendly alternatives in places like urban Manila, people are contend with imagining the heavenly cloud and have no interest with turning the family compute room into a server room. Instead of a fruitful exchange of the physical and digital, a farcical desire to either reproduce/guide natural systems, reinvent them completely, or claim that there is a clear mapping of our digital fabric to the world (Paul McFedries says “the city is a computer, the streetscape is the interface, you are the cursor…”) have led us astray.

An internet has become its own place and it is because of you and me and everyone around us

There is a way to read the internet, a scholarship of which I mostly witness emerging after its microcivilizations have turned into their own histories. I still find it far easier to connect to someone else who grew up “extremely online”, even if they weren’t necessarily coding their own fansites, though it often takes a bit of nudging to get there. I wonder how much of this is because there was only legitimacy when something on the internet was mapped to a physical counterpart. When we failed to recognize digital native experiences for what they are, we fail to keep up with the new modes of being that have emerged within them.

It is insufficient to say that content on the internet, for instance, lives when it is tweeted and dies when it is deleted. Its complex lifespan has begun. It has already been shared in private DMs, mocked on Quote Retweets, screenshotted, edited, what have you—a strange, uncertain record with provenance dependent per platform begins. KnowYourMeme might try to chronicle its legacy, but the internet’s Ship of Theseus is ruthless. Instead it’s deepfried and reimagined and recontextualized. Not native to the internet but accelerated by it is our contemporary ENM-filled dating scene, while it’s slowly getting less and less taboo to say you met on Tinder (a digital place!). Friendships are still a bit strange to me as security has been intertwined with intimacy on social media platforms: close friends or circles as layers of knowing; the discomfort I used to feel when calling people I met on the internet as “friends” when I knew more about their lives and was in closer proximity to them than people who would call me friend in college. I like that in my social contexts, it seems we’ve used the term ‘mutual’ as a step before ‘friend’, something I’d never directly address someone as in person but a healthy position in that vast internet realm of “people I interact with regularly through material we individually put out but haven’t had much direct conversations with”. Too much focus on digital status signals as indicators of actual interest are also the strangest evolutions of these mismatches between reality and the online. A decade ago, I called my friends ‘affiliates’, essentially befriending people by filling out application forms to email to them. There are in-betweens that we can find.

Even beginning with new words (as has already been emerged from the internet) is a productive step. The internet necessitates its own language—perhaps millions of them. While these new vocabularies have to be defined with their own sets of allegories and relations, it is certainly more powerful than mapping our limited lexicons to new human experiences alone.

Perhaps I’m cautious towards all this mapping because I look towards human history: rehousing and urbanization of cities and transport vehicles are often more complex than they seem. The internet is in itself becoming gentrified, such as in its displacement of queer & trans communities and safe spaces in the ironic goal to… make it safer. Capitalization on platforms like Facebook, especially with the immense presence of it in its everyday lives within many countries in the global south, is one form of monopolizing power over sociopolitical & cultural dimensions. Friction is an interesting tool in an internet politic that theoretically presents us the ability to go anywhere at a single click. However, Elon Musk’s Twitter cannot easily be escaped from—the uneven implementation of Mastodon instances and its very premise of decentralization is not what many people want. I can teach hundreds of people how to make websites, but I need to resort to more wide-reaching platforms like Facebook or the email to reach my family and everyone from school. The platform is undeniably toxic and harmful, but has also cultivated interesting corners for care. The trickiness is there’s no way to easily uproot people. There is no one solution or migration that will aid us of our ills—we have now settled, made be. While we deserve better, the greater fear is the newest self-proclaimed savior abandoning us.

With convoluted and scattered process that would make any decently technologically savvy person wince was the act of revitalizing family histories on Facebook groups. Facebook groups, a hellslum but also the space where large-scale community archive projects and self-aware cringey meetcutes alike occur. The best tool is what we have access to, where all our people are. Most of my Philippine Cassette Archive digitization efforts after ripping through Discogs (which is also contains independently uploaded J-cards) is conducted through careful sourcing and open calls on Marketplace and Filipino cassette trade groups, where every decent collector is practically on. While these spaces are not truly safe or lasting, neither are the temporary physical spaces that culture always seems to be most radically bred and shaped in. These spaces have faults but we have made them ours. We have always been communally struggling for our own agencies, pushing the boundaries of our spaces against those in power to generate meaning of our own. The history of media is a history of capturing these objects and shaping them to our own devices, entwined with a history of struggle and organization. The internet no different than the pen, the former just an extension for the latter. I am not arguing for unnecessary struggle to force growth, but I am bringing us to how resilient the internet already is because humans already are. The internet cannot just be uprooted because there exists already hope and history within it. To have faith in a machine you must have faith in yourself. The story of the internet is our story.

The answer to this is not just in tooling or infrastructure, but it’s a good place to start thinking. There is no technological solution nor pattern language to saving the web. Like the awareness of no one-size-fits-all approach for any network or space, a love for what the internet could be prerequisites a careful love to what it already is and how it can differentiate itself from this world. Hyperlocal and folk spaces on the internet can be shaped with as much care and for the scale you dictate, a making of a world. A careful appreciation for the hands, thought, labor, and maintenance that goes into these folk spaces is critical; websites are placemaking, placemaking is worlding, worlding can occur within the vessel of the website. A careful contextual care and sensibility when shaping online spaces

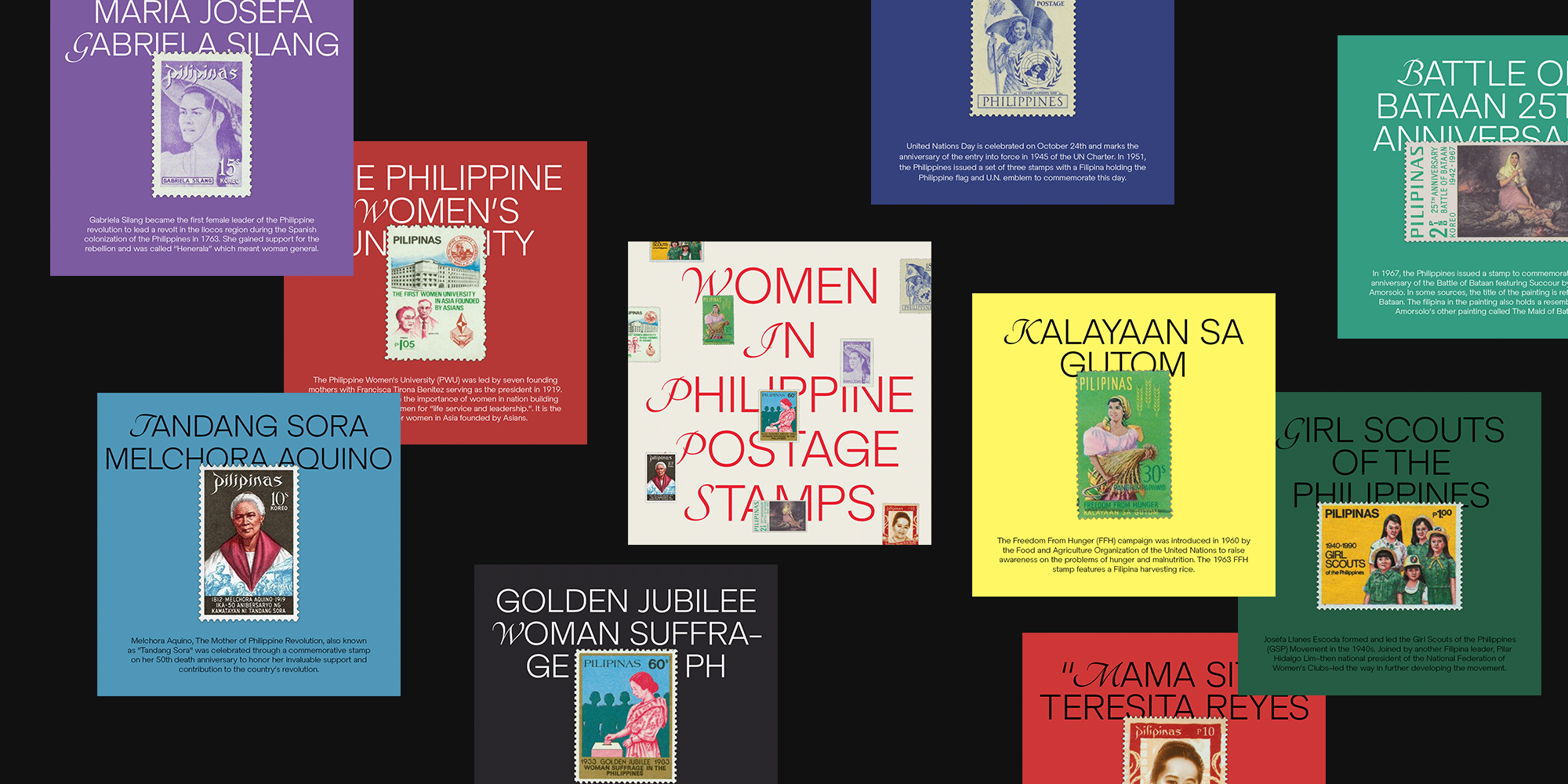

Look to the very ways that those most abandoned by the internet have made their dwelling places. Content moderators, third world laborers, the first female programmers feeding punch cards into machines before women’s work was taken, server workers, call center agents, BPOs, trans folks, women, queer people, teenage girls coding websites—see how the internet has failed them and what the internet needs. See how the internet cannot exist without them. See how they have always been making the internet a place of their own. See how we can no longer talk about the internet without their story, for the internet is theirs.

…machines, people, and processes in an inextricably interconnected and interdependent system” which never goes without “conflict, negotiation, disputes over professional authority, and the conflation of social, political, and technological agendas. Software is perhaps the ultimate heterogeneous technology. It exists simultaneously as an idea, language, technology, and practice.

Nathan Ensmenger, The Computer Boys Take over : Computers, Programmers, and the Politics of Technical Expertise

As politics and legislation become more important in shaping a new internet, we need to look closely to how extant digital constructs and real-world mechanics have responded to one another. Begin with the naive assumption that technology is solely infrastructure, and extend this to how it has taken place in every dimension of our lives.

What I’m keen on is the participatory nature of shaping this imaginary. Everyone should have the capacity to architect their own space on the internet, given technology being a wonderful learnable thing, but in practice this is not what happens. The key part of shaping the internet is the oft underlooked act of examining how we inhabit and dwell in places, how we have converged and formed communities of different scales, the forms of mutual aid and collective care that have flourished against all odds. When I taught code in the Philippines (as I still do, 13 hour gap away), it is consistent in that the most life-changing part is not only technical capability—this is something that anyone can learn at any moment if they choose. It is in this consciousness-raising, this expansion of the internet and of programming, that it can be used beyond corporate, transactional interests—revitalized to express and show love with more ease than before. Like any society, it is not only architects, builders, or engineers that move us towards this collective consciousness. We need people to bring themselves and assume new identities—perhaps where the role of ‘technologist’ is fluid and all-encompassing. Where ‘technologist’ is everyone and anyone concerned with the role of technology, empowered to use it to shape their experience in our pervasive digital world. Spreadsheets will be as potent but more easy to use, but I’m interested in a technological fluency with poetics, love, and radical communal flourishing as its centerpieces. At the core of this human experience, we use technology as a tool to express care & love, to exist together with sincerity.

This is why I am hesitant to trust the faithless, those who have declared this internet broken when I see so many of my people needing it to flourish when the city and real-world offered us no other space. Someone has to want to live on this internet with you. Someone has to see the internet that you imagine.

The internet is not built by an individual and it has become more than infrastructure. It is a reflection of our collective participation and inhabitation. The internet is not the garden I could not access, not a house that I have never built; it is also the private places I reclaimed, all my illegal activities, all the shitty cafes where I found love, all the places where I found respite, all the places made so hostile that I still made for myself. I am the maker of the internet. When I think about indigenous internet practices and the human history I draw from, I first question if indigenous people have access to the internet at all and look towards how they have made their own internet as they were forgotten in its very shaping. We have made our own stories on the internet. Perhaps the internet is like a city in one way: it is nothing without its people.

Technology’s past must be reevaluated in order for better futures to become reality. Despite the promise inherent in digital systems, these tools now work as accelerants – exacerbating social, political, and environmental disasters around the globe. Far too many present and well-intentioned interventions fail because they are developed from systems of privilege and rely on the flawed building blocks of digital societies – identity, connectivity, ownership, and scale. Yet these constructs are fundamentally at odds with most people’s everyday experiences and needs. The opportunities for intervention are similarly disassociated and exclusive, reserved only for members of academia, industry, and media. As a result, those who are in a position to intervene do so with flawed fundamentals, and those who could effect true change are excluded from mobilisation. Until these underlying principles are recognised and addressed, society risks an endless cycle of faulty interventions incapable of altering trajectories in which a digitally driven dystopian future becomes fait accompli. Only through alternative forking can this wheel be broken.

The New Design Congress Manifesto, positing an alternative forking instead of ‘faulty interventions’ led only by those in academia, industry, and media. Similar to the hollow technosolutionist’s dream of poetics on the web, we question whose poetics are valued and what this forking could look like if truly participatory.

An internet where everyone is a technologist

When everyone is a technologist, we move closer to the inherently human nature of technology as a medium and environment in itself. In acknowledging that everyone is already actively shaping the internet, we become better witness to the complexity of the internet’s ecosystems and how many modes of participation exist and are continuously being developed.

My parents will never set up a home server, as admirable as the low tech movement is. They don’t understand the physical form of old media I hold preciously, like my collection of VHS tapes and CDs; they’re not at fault, there’s too much of an aesthetic instead of practical sensibility to their adoption. We are content with the family photos living on a flash drive in addition to a Facebook album; they’re no stranger to understanding data loss, and are at the end of the day, not so different technologists from myself. My home of the Philippines, where people find love and get grades back from their teacher on Facebook Messenger, could not give a shit about Mastodon or other social alternatives; they are willing to risk their security to be in the same place as the people they need. Many of my loved ones are still stunned by how Instagram and Facebook, as transgressive and hostile as they can be designed to be, are the place where they can connect with one another and this world. They do not have time to handwrite blog posts or carve out a specific set of rules like I can with my complex relationship with technology, but they are technologists all the same. We first and foremost need to pay attention to the human needs that underscore technology. Instead of choosing to chastise the vast webs of people who are being inflicted harm by technology for their usage of these tools, we should pay attention to how homes have been carved out in the most unsympathetic environments.

An internet with its own language is a language constructed by its people

Our social networks need to be reframed in a way that allows us to express presence, love, and attention better. Many features are built to optimize attention instead of letting us be sincere in this vast, connective space. While we can try to engage with the internet in a ‘healthy’ way, it is not fair that we are made to carry the burden of these real cognitive and emotional loads as we wait for interaction and care on these networks. The brunt of emotional and psychological pain is on us, yet many times humans are not trusted as true agents or intelligences when we deserve to be able to best serve ourselves. This is not a solitary act: finding ourselves in healthier spaces and communities reminds me of leaving toxic, repressive spaces in-person. This is why I push towards resisting what the image of the web is as a first practice to encourage new imaginaries and better futures, in the same way that we can create our own sanctuaries in the real world. This is all incredibly easier said than done.

We need to forge more ways to carve an internet that is ours. The act of forging begins not with a catch-all tool, but with people. It begins with faith in how humans have always made the most of where they are. The tools and capacities are already there, but there are decades of injustice that we need to begin rewiring, and decades of placemaking that we need to take more seriously and draw from. We ourselves should move towards the very possible engagement with the internet (even the most puerile platform). Tenderness is already there. People have, against all odds, offered their sincere selves. That I grew up in an internet of love and understanding in the worst platforms imaginable because humans have made it this way.

There is no ‘pure’ internet to find. There is no secret innovation, platform, or tool that will rid us from the failures of the ones before. There is no one machine that reproduces the feeling of being loved and being understood. There are only the people behind these machines and their intentions — their love permeating through no matter how desolate the body has become.

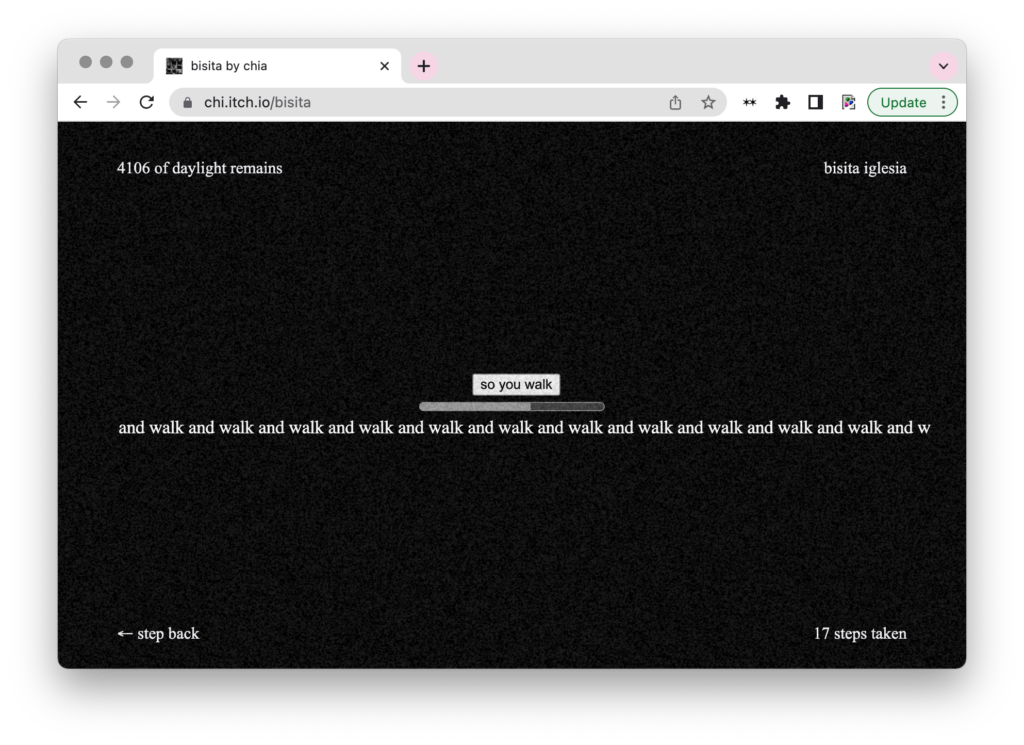

There is no one alternative fork that rids us of the sociopolitical tensions and compromises necessary from the infrastructure that makes networking at this scale possible. We forget that technology is a human act. There is no alternative future but the ones we are already acting and walking towards today.

I’m wary towards this picking for ‘purity’, as if there is some recipe or formula or platform that has offered the ideal infrastructure for care & safety when the magic of the internet is in its versatility, which is how we have made space within it in the first place. We caution against technosolutionism infiltrating human questions of love, gathering, and tenderness. All our definitions of ‘organic’ differ, our framings of the internet as a utility shift, what others desire as ambient others would prefer as explicit. There is no likening to the internet to any one public utility or organism—it would be a disservice to both the natural world and this new internet we have made. The internet is brutal and ugly and imperfect, and while the technosolutionist will partially correctly say that it was and never is ours—many human perspectives, I’d counter, will say that against all odds they have made it theirs already. How have they made it theirs? How have humans always been making this world theirs?

This story is about transformation of the human through the digital. But which human?

Maya Indira Ganesh

We cannot just abandon the internet and claim that it didn’t have the space for us if we didn’t try sharing in this space ourselves. I see these conflicts a lot in the quest to interrogate a ‘pure’ Filipino identity in design or technology, operating atop colonialist ideals and Western signals. Even by the Filipino name, derived from our archipelago’s title of Las Islas Filipinas is a product of colonial times. Every modern day human is now a cyborg. It is futile to attempt to identify the ‘pure’ internet or identity—it does not exist. The purity is in how we have been remaking ourselves over and over, how the internet did not begin with us and how we have always been inserting ourselves.

How can we construct a new world when we don’t know what the people we love need? How can we claim to pioneer a new place with new technologies and machinery without the humanity in these efforts?

***

At its core, the destruction these machines have brought unto us are self-imposed. In the time of techno-capitalism, our networked machines only accelerate a spatialization of thinking. As we employ these accelerants, we must be cautious of the ideologies we’re reinforcing and where our technologies draw from. What does ‘human-first’ mean when we discuss technology? It is not a self-evident category, but an amorphous political and ideological tool that has long been used to maintain existing hierarchies, excluding some people to benefit others. Humane’s ambitious mission of building innovative technology that feels “familiar, natural, and human” has equated “humane” with “seamless with the real world” powered by artificial intelligences with their new devices, claiming that computers can drive culture. Technology only reproduces natural social ails, divisive in access instead of offering us agency. The human act of culture generation is offloaded and we wonder why we feel so disconnected. A fetishization of the natural world confuses the familiar as intuitive at best, and worse, disregards why we have abandoned old models of organizing for the new. Local structures and ancient methods have evolved for reasons, and the internet is a fascinating space that can remove boundaries in new ways — as long as we offer it with meaningful forms of inhabitation.

Instead of the lofty, dangerous dream of a perfect singularity of experience, let us stop dreaming. There is no one resolution. Know that we already inhabit a polycentric internet with diverse worlds. Already. An act in the present.

Places with pluralities include how humans have networked and captured the most infrastructurally sordid of places. Pluralities that have come forth, principled with offering us genuine agency in choosing our modes of participation. Pluralities of the internet that recognize what modes of being have only existed on the internet, and a dignifying of these ways of being. Pluralities that work against the romanticized metaphors of place that disregard the unique nature the internet has given us. Pluralities that recognize the histories of abuse and exploitation in any system of gathering, including that of the internet. Pluralities of the internet that understand the complexity of human relations and being, of modes of gathering. Pluralities that understand how the internet has become its own, many of our owns, against all odds.

“Seeing come before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.

Ways of Seeing

But there is also another sense in which seeing comes before words. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.”

Do you believe that there is already love on the internet? Do you believe that the internet is its own place?

An internet where we see the ways of being

In our power struggle for a poetic web, we need to begin by shifting power away from the men who make the select few tools & decisions that power our world and reclaim the true agency that machines have given us. We begin with reclaiming the agency in imagination. We are already loving, being, connecting, ourselves, placemaking on the internet—but this internet will only be ours once we all take upon the name of technologist. This naming is all we need to do.

All of us, by every form of participation, already shape the internet. Humans are resilient and so is the internet. Humans are loving and so is the internet. Humans are culture and so is the internet. A computer is a vessel, a tool, only a carrier of human belief and thought. When we recognize that a diverse participatory imaginary is key to constructing this future, we will better thrive. There are already tools and people who can drive the infrastructure, people who steer culture, people who live and inhabit these dwelling places.

The technosolutionist must see the present ways people have been dwelling within the internet. The promise of the internet is not waiting; it is in how people are actively shaping it.

Before the technologist looks, they must see and make credible in their own vision the faith we have put in our tools—only then may they decipher how the tools have failed us, and what we need.

The technologist must encompass all those who inhabit the internet; not the detached figures who shape it. The bricklayers who gate the internet for us and are often the most gated; those who don’t know what the internet even extends to; those who have been failed by the internet but return to it anyway; those who see the internet as a plaything and those a necessity; those who struggle with the cyborg body and attempt to distinguish the physical and digital self; those who do not know what they need or what they could become. Once we are all creators, there will be no gods.

Technology is a human act. There is no secret software or innovation that will move us there. Just a history of how we exist, evolve, and occupy space. Politics reinforcing itself on both our physical and digital bodies and environments. Technology is a continuous act. Technology is manifested in the ways we relate to each other. Technology that can absolve the failure of one technology before, and ideally should not exacerbate the injustices perpetuated by the last. Technology that is alive because we are already dwelling in it. Technology that is a question because of how differently we dwell in it. We are living in it. It is just as easy of a thing we can make, as we recognize and name how we be.

We have been interacting with the internet for decades, and its older forms for centuries.

That there is a already a world of being we can draw from. That there is no purity. There is no new platform or network that will save us, only us saving ourselves.

The internet will only truly become a place once we recognize it for what it is. A place that cannot map to a city, a garden, or a tree—but might turn to their principles and apply them in new ways—once that should swear towards radical reinvention, not the failures of the old. A blurry dissolving of selves and areas. A place where all the people I love are here at once and also all apart. A place that freed me from the real world. A place that is not free from the real world. A place built atop of the labor of human hands, where the act of laying down wire is no less holy than writing the lines of code we are in.

I’m conscious of the internet, and a turn in the internet’s consciousness made these new imaginations of the space possible. Many times is the act of imagining just an act of seeing and naming. We have always been laying the groundwork before us. A constantly active act.

We must be conscious to legitimize the current ways of being and loving. This legitimization is an act of seeing as people are, to practically participate in the formation of the web by learning from its inhabitants, to shape it together and form a cogent understanding of what we need. That we pay respect to how those most marginalized from the internet have built their own havens—the work of disenfranchised communities, the women who have been written out of its history, the technologists of all levels who risk it all for the safety and security on the internet. Technology shaping starts with becoming.

We see the resilience that has carried the internet today, why it is a place still worth fighting for. Numbers alone cannot tell the story of our relationship with technology; there is a history of harm and love and being and reclamation. To move this space forward

The internet has become its own place and needs to be seen and recognized for the place that it is. There is no essence or promise but what we shape. The internet is no garden you have ever seen before, the internet is everything at once, the internet is beyond what you see so you must always be looking.

That we are all technologists. That we are all in relation to each other. That technology is just a series of how we are being.

That the shaping of the internet we want is a human act.

I want you to see the internet that is mine and how you can live in it with me, and how there is an internet that is yours that is all around you.

I’ve kept this blog since I was sixteen as my own form of radical being. I feel safe enough to be naive here, in this alcove atop of servers not my own, but know that my caretaking is always extending and seeking more agency. I talk about carving spaces on the handmade web to artists & technologists who speak languages closer to mine, am beginning to assemble DIY machines, and return to publishing & teaching people how a computer works. Sometimes we begin with how to think of the mouse as an extension of the body, other times how to reclaim agency and autonomy on the internet as a form of will, and others a glorious surrender to human intelligences that has given us these tools and how we can continue the human act of wielding and creating. Most of the times it is just telling someone that this computer is now an extension of themselves and they simply must learn to wield the limb: they will learn, they do not care, they have no insight to the market, they risk it all, they teach themselves at 80 when their eyesight is blurring so that they can see someone they love and be with someone they love.

And they are why we still build technology. They are why there is still love here.

There is no one solution I can offer, just a way of seeing where they are and what the computer & internet can do for them. They are all technologists to me.

Anyone who teaches code and computers knows the struggle in finding the perfect metaphor to explain its logic. Baking instructions, a series of steps, a variable as a vessel. The activity always boils down to you, the human, and what you would like to will.

If there is a metaphor for the internet at large, its grand scale of immediacy and intimacy which we’ve seen every precedent for but also so little, it might be one of the Aleph. Where we see everything at once in its unbearable brilliance and humanity, an infinite thing of human life and experience that we would struggle to recount, the unending eyes across an unending feed amongst deaths and births and hate and love, the rotting links, the act of creation against the endless swarm of entropy, the decaying messages, the decaying self, all your fragmented parts, all the areas that are timeless and spaceless and know no boundaries, all that is now in our feeble attempt to preserve our own self, and you, and yourself.

On the back part of the step, toward the right, I saw a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance. At first I thought it was revolving; then I realised that this movement was an illusion created by the dizzying world it bounded. The Aleph’s diameter was probably little more than an inch, but all space was there, actual and undiminished. Each thing (a mirror’s face, let us say) was infinite things, since I distinctly saw it from every angle of the universe. I saw the teeming sea; I saw daybreak and nightfall; I saw the multitudes of America; I saw a silvery cobweb in the center of a black pyramid; I saw a splintered labyrinth (it was London); I saw, close up, unending eyes watching themselves in me as in a mirror; I saw all the mirrors on earth and none of them reflected me; I saw in a backyard of Soler Street the same tiles that thirty years before I’d seen in the entrance of a house in Fray Bentos; I saw bunches of grapes, snow, tobacco, lodes of metal, steam; I saw convex equatorial deserts and each one of their grains of sand; I saw a woman in Inverness whom I shall never forget; I saw her tangled hair, her tall figure, I saw the cancer in her breast; I saw a ring of baked mud in a sidewalk, where before there had been a tree; I saw a summer house in Adrogué and a copy of the first English translation of Pliny — Philemon Holland’s — and all at the same time saw each letter on each page (as a boy, I used to marvel that the letters in a closed book did not get scrambled and lost overnight); I saw a sunset in Querétaro that seemed to reflect the colour of a rose in Bengal; I saw my empty bedroom; I saw in a closet in Alkmaar a terrestrial globe between two mirrors that multiplied it endlessly…

Unlike the Aleph, we are constrained to the imagined universe—the one we have chosen to share on the internet. In our small human experience, this might suffice for what is beyond our imagination. Let’s begin there. What does humanity see and envision that you don’t? What can we will of this space that we all share? How do we will it together?

Let’s start by being.

And this time, we don’t have to go out and pretend like we’ve never seen it.